The Perfect Blend of History, Stunning Landscapes

and Challenging Flight Operations

G’day, folks!

You’ve come to just the right place if you’re looking for an adventure through the great mining industry in Western Australia. We’ll be covering all aspects of the entire operation, from the origins of some of the resources mined, to their discovery, shipment and export to the rest of the world, and of course, the flying operations. You’ll see just how much rich history and legacy lies behind these FIFO flights!

But First, What is FIFO?

Fly-In, Fly-Out arrangements are a type of transportation arrangement where as the name suggests, workers fly into their workplaces on aircraft, and fly out at the end of their work shift. These are typically in place when work needs to be completed at a remote location far from any major town or city, and workers tend to stay for a week or two at a time. While there are many places in the world with such arrangements, no one does it bigger and better than the resources industry in Australia.

Mining

Mining in Australia has a very long and rich history beginning from as early as the 1800s. Gold, iron ore, lead, bauxite and various other minerals were and are to this day, still mined in large volumes in Australia. It constitutes a significant portion of the Australian economy, accounting for 14.3% of Australia’s economic output, and making up a very sizeable 69% of the country’s export revenue. Key markets are to China, the US and Europe (add more data). Approximately 311,000 people are employed in the industry, many drawn by the high salaries, which are a fair amount above the average in Australia.

It’s also a largely bulletproof industry from the traditional economic threats that cause many large industries to shrink. Crises such as the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS and many other global economic downturns had a minimal impact on many aspects of the mining industry. Contrary to what some may think, mining in Australia is not a sunset industry – the massive economic growth of China and hence the huge boom in infrastructure projects in the last few decades sparked high demand for iron ore, which is one of the key components of steel. Among many other natural resources such as gold and silver, iron ore remains one of the key products mined in Western Australia, with an estimated 60 years remaining of production available. Looking further into the future, there remain large undiscovered deposits of rare earth minerals such as lithium, nickel and cobalt, which are critical for the manufacturing of many advanced electronics, playing an important role in the push towards decarbonisation and environmental sustainability.

https://www.ga.gov.au/education/minerals-energy/australian-mineral-facts

How large?

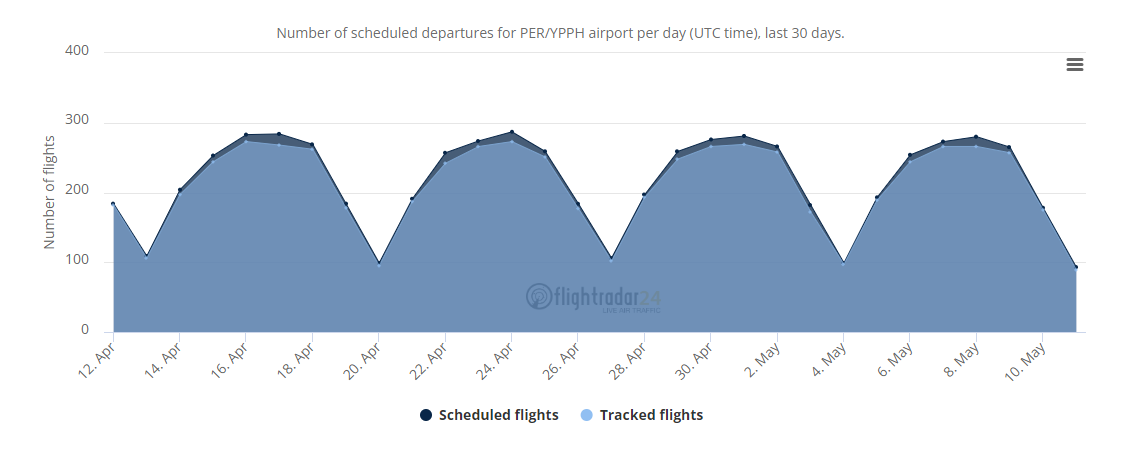

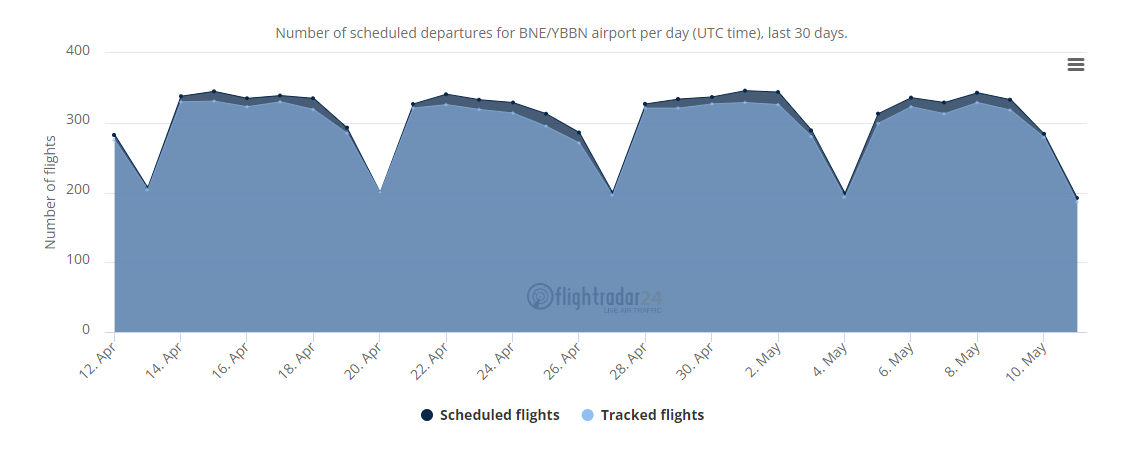

There are 3 major airlines that do FIFO flights – that being the Qantas Group, Virgin Australia and Alliance Airlines. Alliance Airlines has a stronghold in the Queensland FIFO scene, while Virgin Australia and QantasLink take the majority in Western Australia with over departures a week. Of the 1,486 departures tracked by Flightradar24 from Perth airport during the week from 05 May 2024 to 11 May 2024, a large proportion of these flights are exclusive-charter FIFO flights, and an even larger proportion are public flights that mainly carry FIFO workers, such as those to Paraburdoo operated by Network Aviation on behalf of QantasLink.

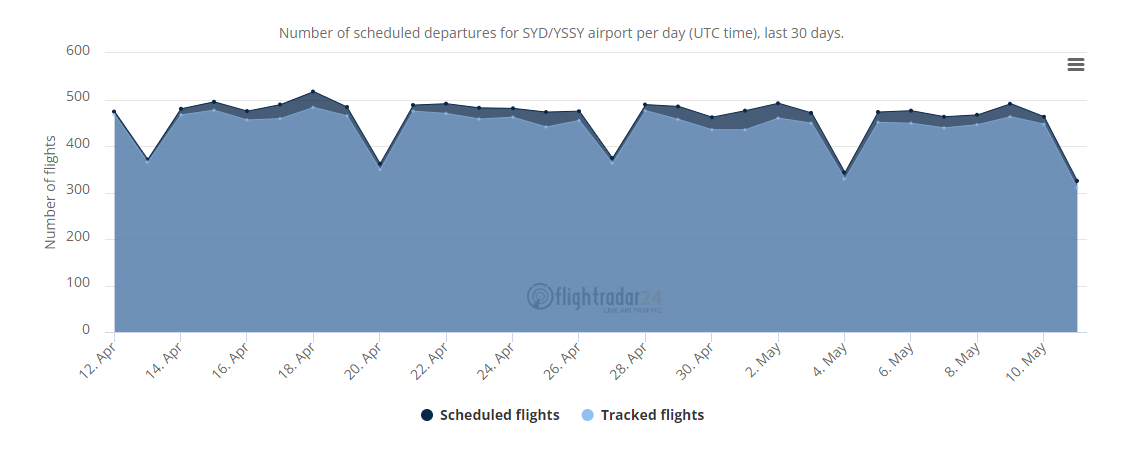

You can see evidence of this from the 4 graphics below courtesy of Fightradar24, which show the general patterns for the number of tracked departures at Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth across a week. Perth, with a large fraction of its departures being FIFO traffic, sees a very significant dip over the weekends as compared to Melbourne and Sydney. Brisbane sees a slightly larger dip than Melbourne and Sydney, and that is because there is indeed also FIFO traffic out of Brisbane, albeit at a smaller scale than Perth.

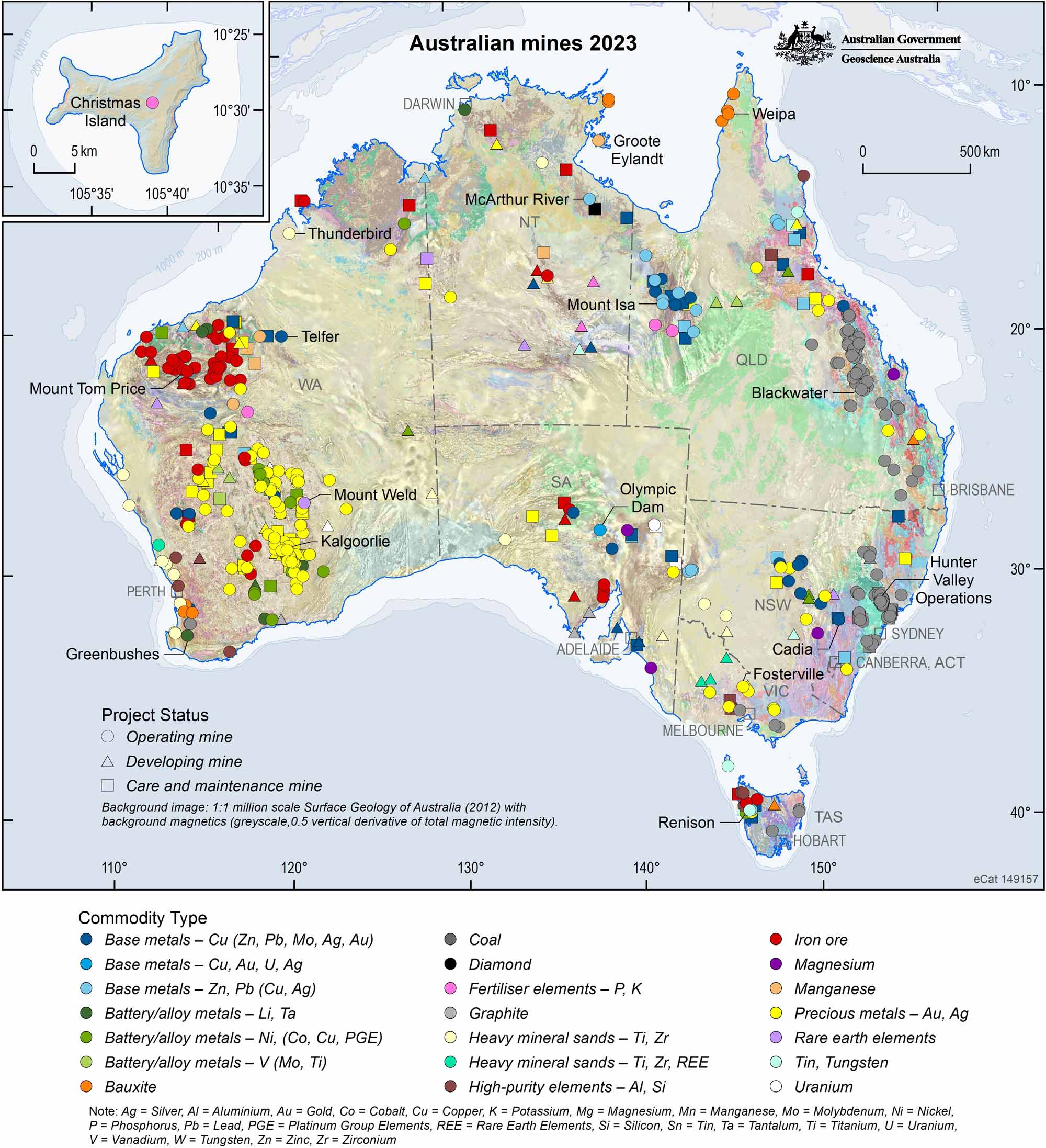

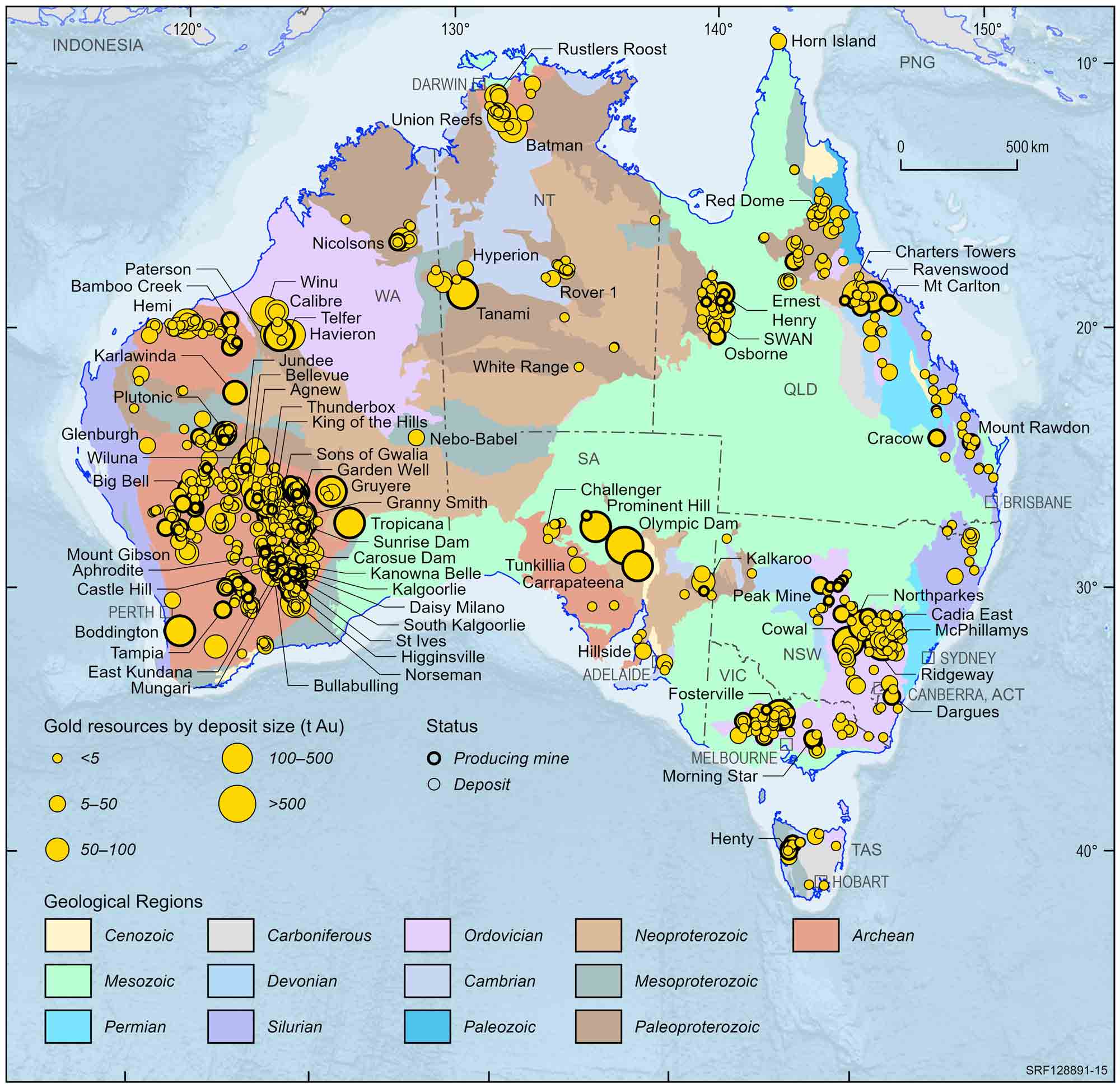

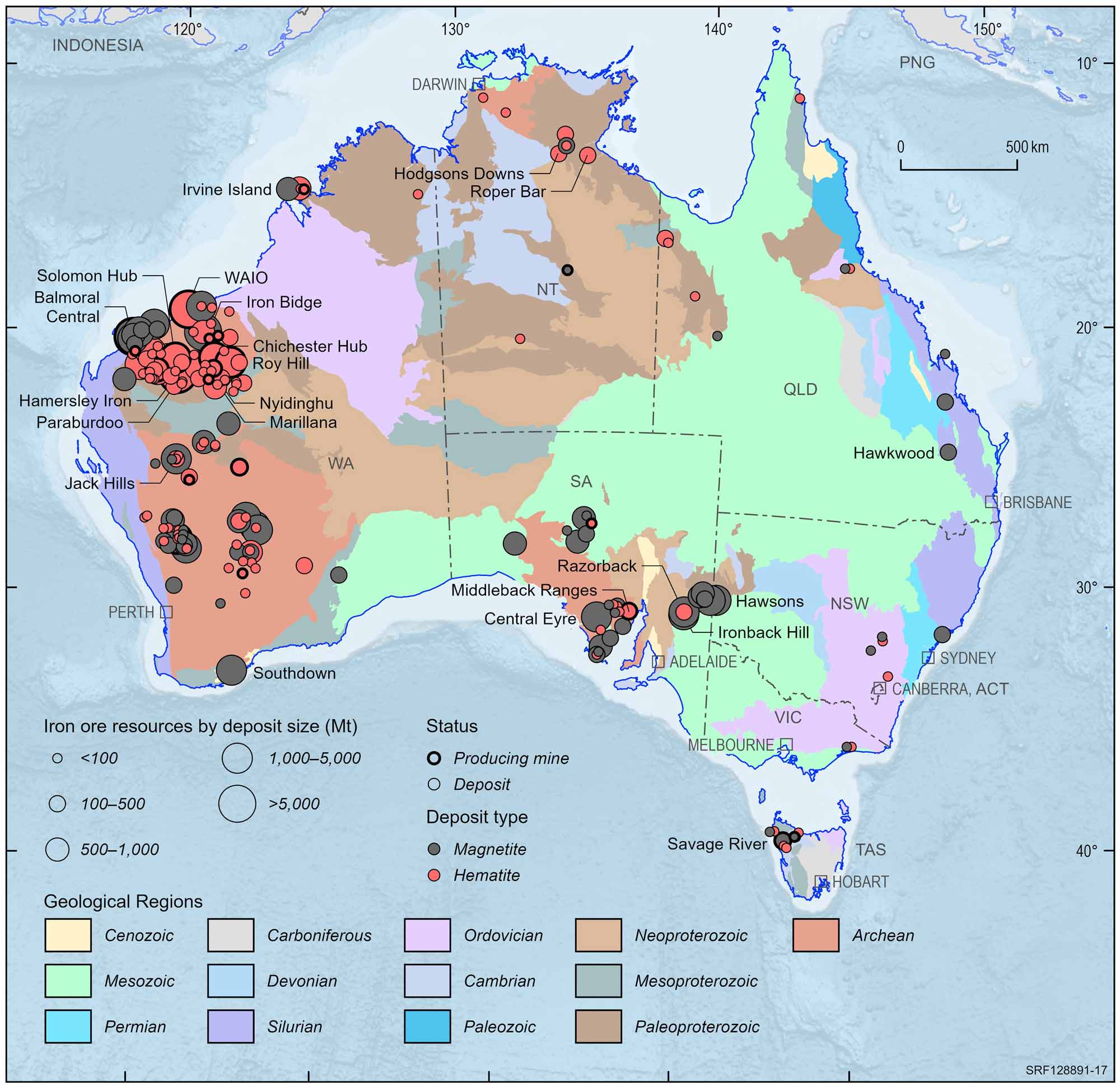

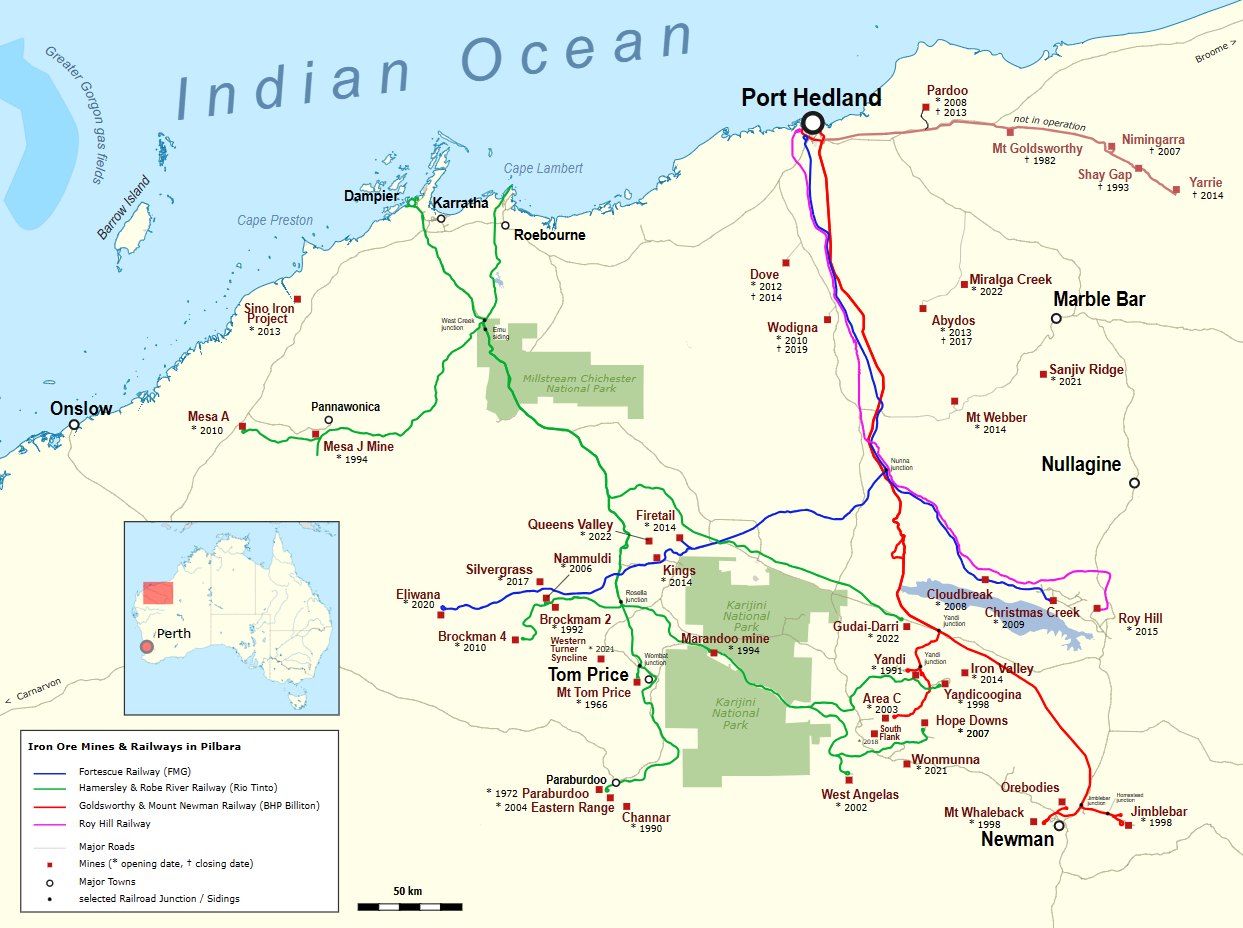

As you can see, while mine sites are distributed all across Australia, Western Australia has the largest share of them, with the vast majority being iron ore mines and precious mineral mines. This is in contrast to the coal mines that we see in Queensland and New South Wales. This is a large contributing factor to where the FIFO ports are located – an airstrip capable of supporting jet aircraft operations takes a large sum of money to construct and maintain, and these ports must be able to justify their cost of operation by bringing in large amounts of revenue and cost savings in doing so, which we will analyse in greater detail below.

While FIFO does exist in Queensland in particular out of Brisbane airport, the mine sites in the Pilbara and Goldfields-Esperance regions of Australia are much more remote than the sites in Queensland and New South Wales, which are comparatively closer to populated places, as shown on these maps below from the Geoscience Australia Portal. Unfortunately these are the best images that I could get, so here’s the link if you’d like to explore the map in greater detail. Simply open the layers dropdown and select the different items you’d like to have displayed, such as operating mines, populated places etc.

The large circles, triangles and squares represent the mines, colour-coded according to the nature of resource mined. The populated places are the small yellow circles with text next to them. Any text that you see in the photos above, bar the state names, represents a populated area with a permanent population. If you’d like to zoom in and read the names of the places, do visit the site itself.

Why FIFO?

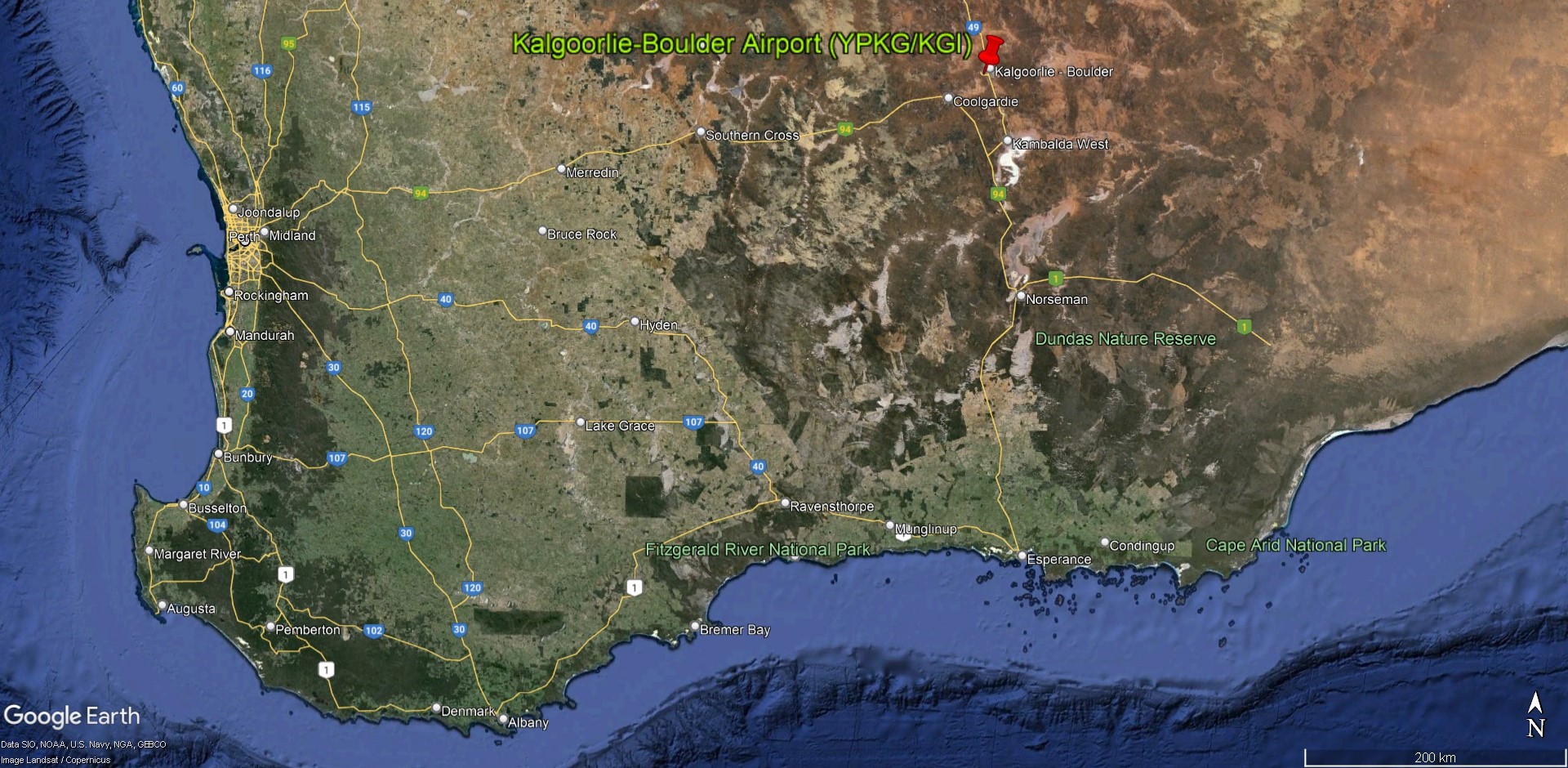

Let’s take a look at how long it would take to get to one of the closest FIFO ports to Perth, Kalgoorlie, which is located 550 kilometres away as the crow flies. We’ll consider the 3 main ways of getting there – by car, train and air.

The 600-kilometre drive via the Great Eastern Highway would take between 6.5 to 7 hours, while the train journey would take approximately 7.5 hours. The flight time between Kalgoorlie and Perth itself is usually in the region of 50-55 minutes, and including taxiing times, as well as budgeting 2 hours to spend at the departure and arrival airport leaves us with just over 3 hours of total travel time. We’ll add another 30 minutes to account for the commute to the airport as well as any unforeseen delays. That gives us a lead of at least 3 hours over the next fastest alternative when travelling by air.

A company when deciding whether to opt for a bus service or air service will undoubtedly make the decision almost exclusively on which option is the most economically sound, which is good news for us as we can then understand why when looking at the data. On average, FIFO workers are paid an hourly wage of 50 AUD per work hour, which we will view as the company valuing every hour of useful work from an employee being worth 50 AUD.

FIFO workers queueing up at Perth Airport’s Terminal 4 for an early morning flight off to Newman. You can spot them fairly easily by their characteristic high-vis jackets, safety pants and thick work boots. Image courtesy of The West Australian.

An average cost for a single person booking a regularly-scheduled return flight from Perth to Kalgoorlie is about 500 AUD. Now, these mining companies that charter these flights will definitely have contracts with the airlines, and the prices they are quoted to ferry an employee will certainly be significantly less than 500 AUD per passenger. By comparison, a return bus trip would cost 200 AUD per passenger. Now, let’s say a company decides to switch over to bussing their workers in and out instead of flying them. This would reduce the number of working hours per employee by 6 hours every round trip. Yes, they would have saved 300 AUD per worker, but in losing those 6 hours of work, revenue has now gone down by more than 300 AUD (6 hours multiplied by 50 AUD an hour), since the company will surely need to make more than 50 AUD an hour from a worker’s work to remain open for business. Even if they chose to instead hire more manpower to make up for the 6 hour shortage, which is what would be done in reality as these mines operate 24/7, there will be extra costs associated with the transport, lodging, onboarding, food etc. of the extra manpower needed.

Additionally, the 500 AUD and 200 AUD are fares as quoted for a single consumer purchasing a return ticket. A large mining company like BHP or Rio Tinto will surely have contracts with the airlines or potential bus operators that will cost significantly less for the transport of their workers, since FIFO traffic on these routes makes up the majority of the passenger load on each flight. For our analysis, this means less cost savings for the company if the contract prices are the same fraction of the consumer ticket prices. To illustrate with a hypothetical example, if contract prices for both bus and air services were 50% of the consumer ticket prices, that would mean a transport cost per worker of 250 AUD by air and 100 AUD by bus, meaning the cost savings to the company that switched over to bus transport would now be only 150 AUD. This further skews the equation in favour of flying the workers in.

Furthermore, I’ve picked Kalgoorlie for this analysis, which is the closest FIFO port to Perth. For a company looking to transport their workers to FIFO ports further out such as Port Hedland or Newman, the time savings are much further skewed, so much so that it would simply be unrealistic to transport workers by road. The drive to Newman and Port Hedland would take upwards of 12 and 17 hours respectively, compared to a flight time of approximately 1.5 hours to Newman and an extra 15 minutes to Port Hedland. Add in the fixed extra 2.5 hours to account for the checking in, taxiing, delays and commuting to the airport, and you can quickly see why it’s an absolute no-brainer to fly workers in, at least if an airport capable of accepting jet aircraft already exists at the intended destination.

No Airport? Just Build One, Yeah?

Now, the interesting bit comes if there was no airport already in existence at the mine site, or if the existing airstrip needs to be upgraded to support jet service into the airport. Many of these mine sites were discovered and developed between the 1980s and the 2010s, before any sort of civilisation and hence any form of an airport existed in the vicinity of the mines. And so we want to answer the question – how much extra would it cost to construct an airport and the necessary infrastructure to support it completely from scratch, certify it, and operate it, solely for the purpose of FIFO operations?

Unfortunately, there is no data available on the cost of construction and operation of FIFO ports that were purpose-built to support the FIFO operations, and operated by the mining companies. Examples of such airport include Fortescue Dave Forrest Airport (YFDF) by the Fortescue Metals Group, as well as Roy Hill Ginbata Airport by Roy Hill Holdings. Their financial statements do not have a section dedicated to the cost of operations of their airports.

Nonetheless, we can build a good estimate by looking at the financial reports of airports that are of similar capacity in Australia, especially those in Western Australia and that see good amounts of FIFO traffic. Newman and Port Hedland are the top 2 picks in Western Australia, while Proserpine and Launceston offer good insight with further detail.

Based on the reports from the airports mentioned, we can estimate that for the amount of traffic that these private FIFO ports receive, which is between 2 and 10 flights a day, the cost of operation is likely to be around 2 million AUD a year, with airports that see more traffic like Boolgeeda possibly seeing up to 5 million AUD a year, including the depreciation over its useful lifespan from the construction of the airport itself. This takes into account that these FIFO ports have extremely minimalistic designs, with a simple 2,000-metre runway, an apron enough to fit 2 jet aircraft, and a very small terminal that simply serves as a waiting and check-in area with no extra frills. While this may still sound like a gargantuan amount of money, we must put things into perspective, realising that each of these corporations that own and operate the airports are generating billions in yearly earnings. As an example, the third-largest mining company in Australia, Fortescue Metals Group, reported earnings of 9.96 billion AUD in 2023.

On average, each of these private FIFO ports see yearly passenger movements in the range of 100,000 to 150,000. This would mean each round trip per passenger costs between 20-50 AUD. This is likely a fraction of the cost per passenger to fly them there, which makes the construction of a new airport next to the mine sites simply for the sake of supporting FIFO operations viable, as the overall cost to the company with alternative means of transport is far greater than the total cost of sustaining FIFO operations. This explains why we see so many airports springing up around the mine sites, with many of them located less than 100 kilometres away from each other.

Note: If you think about it, this conclusion could already have been reached, simply by realising the fact that almost all airports are for-profit organisations. At smaller airports, most of the revenue comes in the form of aeronautical income, which are things like passenger surcharges, landing fees, as compared to non-aeronautical revenue, such as rental income etc. This means that in order to keep the lights on at say, Kalgoorlie Airport, the costs associated with the construction and operation of the airport would already have been included in the flight ticket prices. Some of this may be indirectly absorbed by the airline, while others may appear in the form of passenger surcharges and taxes. And hence, it won’t cost that much more, on top of the flying operations, to set up and run an airport, as long as you have the financial capital to do so, and have enough passenger movements to keep the costs per passenger reasonable. It would be a huge waste of money to set up an airport just to have one flight come in per year!

In the Sim

One of the great things about doing these FIFO flights is the absolutely stunning scenery that you get to enjoy. To quote VATPAC’s description of their FIFO Downunder event –

“You won’t believe your eyes when you see the red deserts that are so red, they make Elmo blush! And let’s not forget those extraordinary rock formations that’ll have you saying, “Who needs abstract art when nature’s got it covered?”

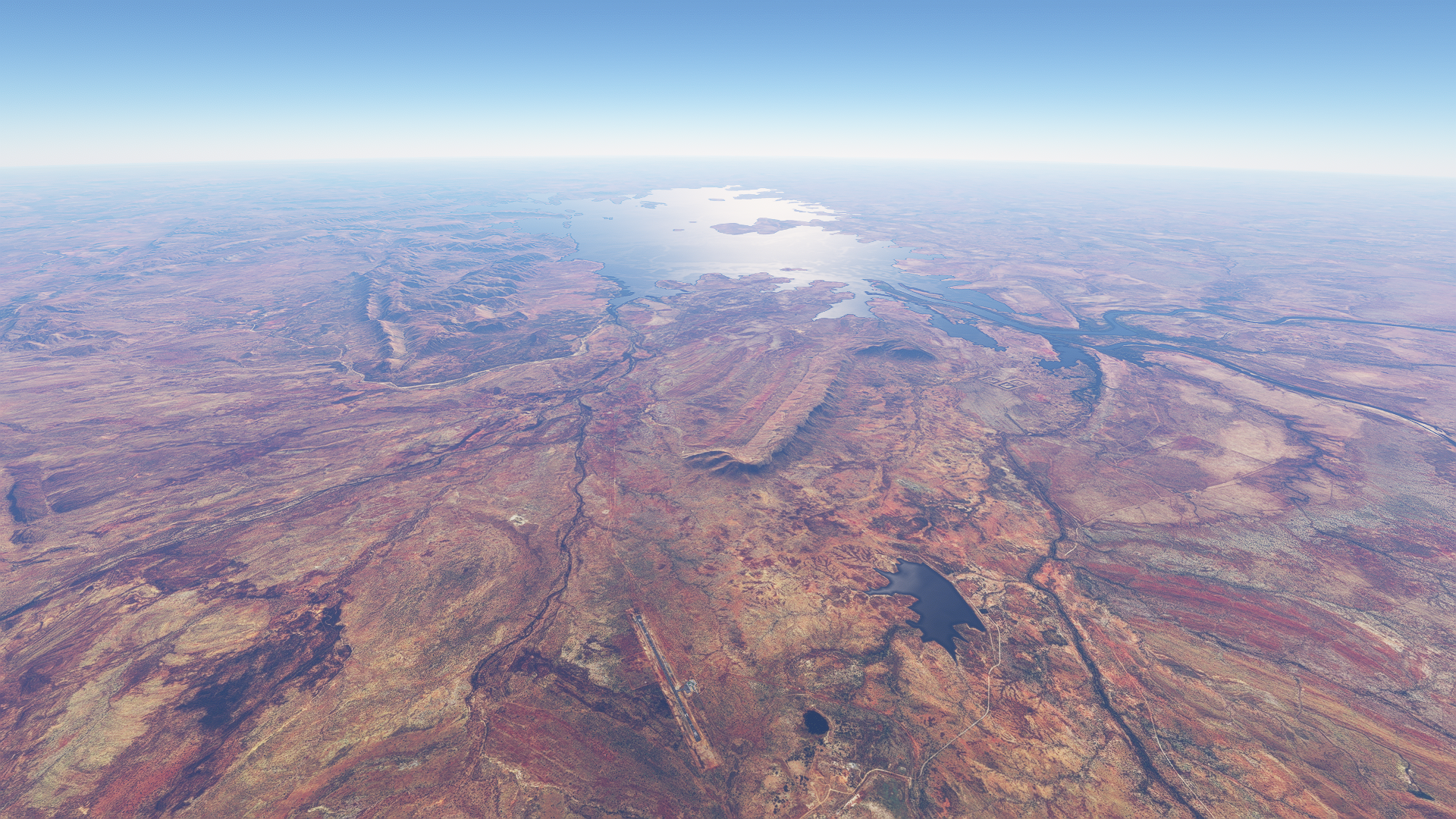

Indeed, the scenery is some of the most stunning and unique in the world. Red desert stretching for miles on end, with various rivers and lakes winding through the lands, some dried, some with beautiful turquoise colours. The entire plain is a canvas for a the painting that Mother Nature has crafted over hundreds of thousands of years. Every where you look, there’s not a single boring angle that you’ll find! The satellite imagery is also crisp and high-resolution, and doesn’t suffer from “patchy” areas that one might see in areas of extreme latitude or places like mainland China, where satellite image coverage is not as good. Well, I’ll let the pictures below do the talking – you be the judge!

West Lyons River region, at the northern edge of the Mid West, bordering the Pilbara

On climb heading south out of West Angelas Airport en route to Perth over the Angelo River in The Pilbara

Near Mongers Lake, south of the border between The Mid West and The Wheatbelt

On the way to Solomon Airport at Flight Level 370 just south of the Gascoyne River, which is the longest in Western Australia at 865 kilometres in length

The other wonderful part is that the large majority of these FIFO airports are freeware sceneries available for download on flightsim.to! The following list of sceneries are available for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 (MSFS 2020), and with the exception of Karratha (YPKA/PKA), are all completely free, having been created by talented volunteer creators such as CoolGunS and Bindook. This list below currently contains airports in Western Australia (WA) that see FIFO service by the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737NG, which are currently the only 2 high-fidelity airliners available for MSFS 2020 that serve these routes in real life. JustFlight will be releasing their Fokker 70/100 addon likely some time later in 2024, which will open up many more routes to airports such as Paraburdoo, which is already in the base simulator as part of World Update 7: Australia. I have included a separate list for these airports too.

The two lists are, as of 13 May 2024, accurate, though with new sceneries being published and equipment swaps, mine closures and the likes, the entries may very well change over the course of a year or two.

FIFO Airports in WA Serviced by Boeing 737NGs and Airbus A320s:

1. Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport (YPKG/KGI)

2. Leonora Airport (YLEO/LNO)

3. Argyle Airport (YARG/GYL)

4. Newman Airport (YNWN/ZNE)

5. Ginbata Airport (YGIA/GBW)

6. Christmas Creek Airport (YCHK/CKW)

7. Fortescue Dave Forrest Airport (YFDF/KFE)

8. Gudai-Darri Mine Airport (YKDD/OOD)

9. West Angelas Airport (YANG/WLG)

10. Wodgina Airport (YWGA/QBW)

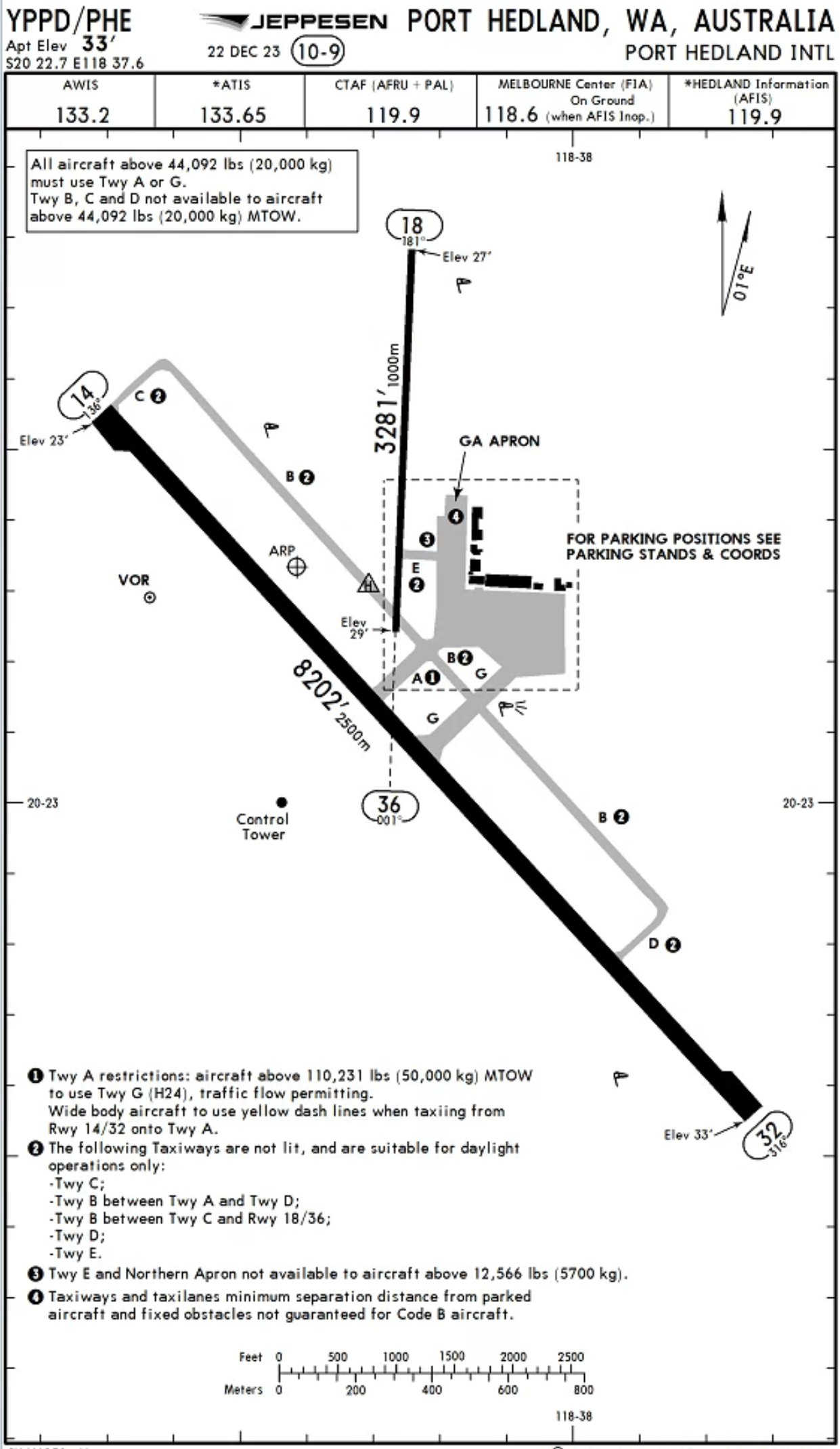

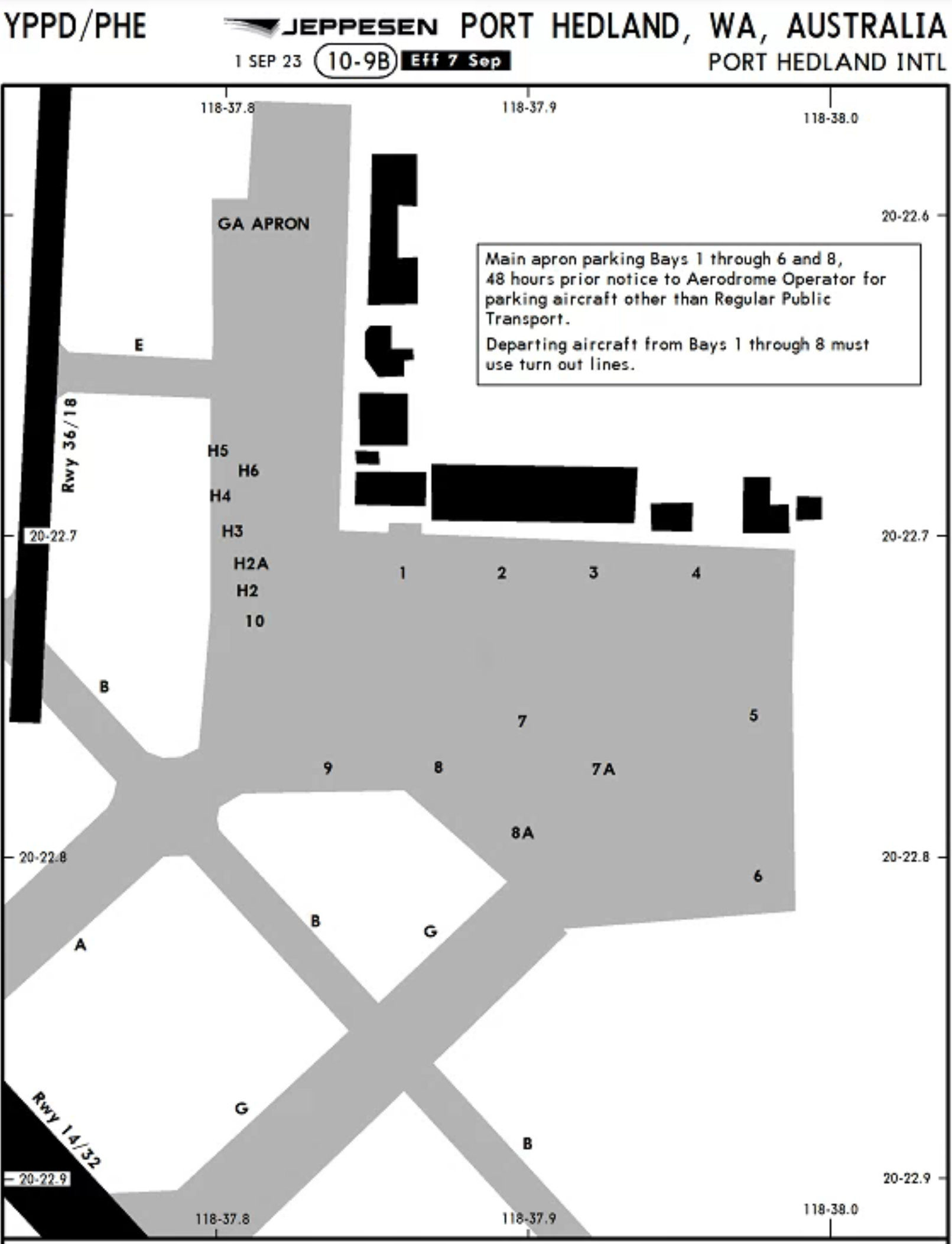

11. Port Hedland International Airport (YPPD/PHE)

12. Solomon Airport (YSOL/SLJ)

13. Boolgeeda Airport (YBGD/OCM)

14. Karratha Airport (YPKA/KTA)

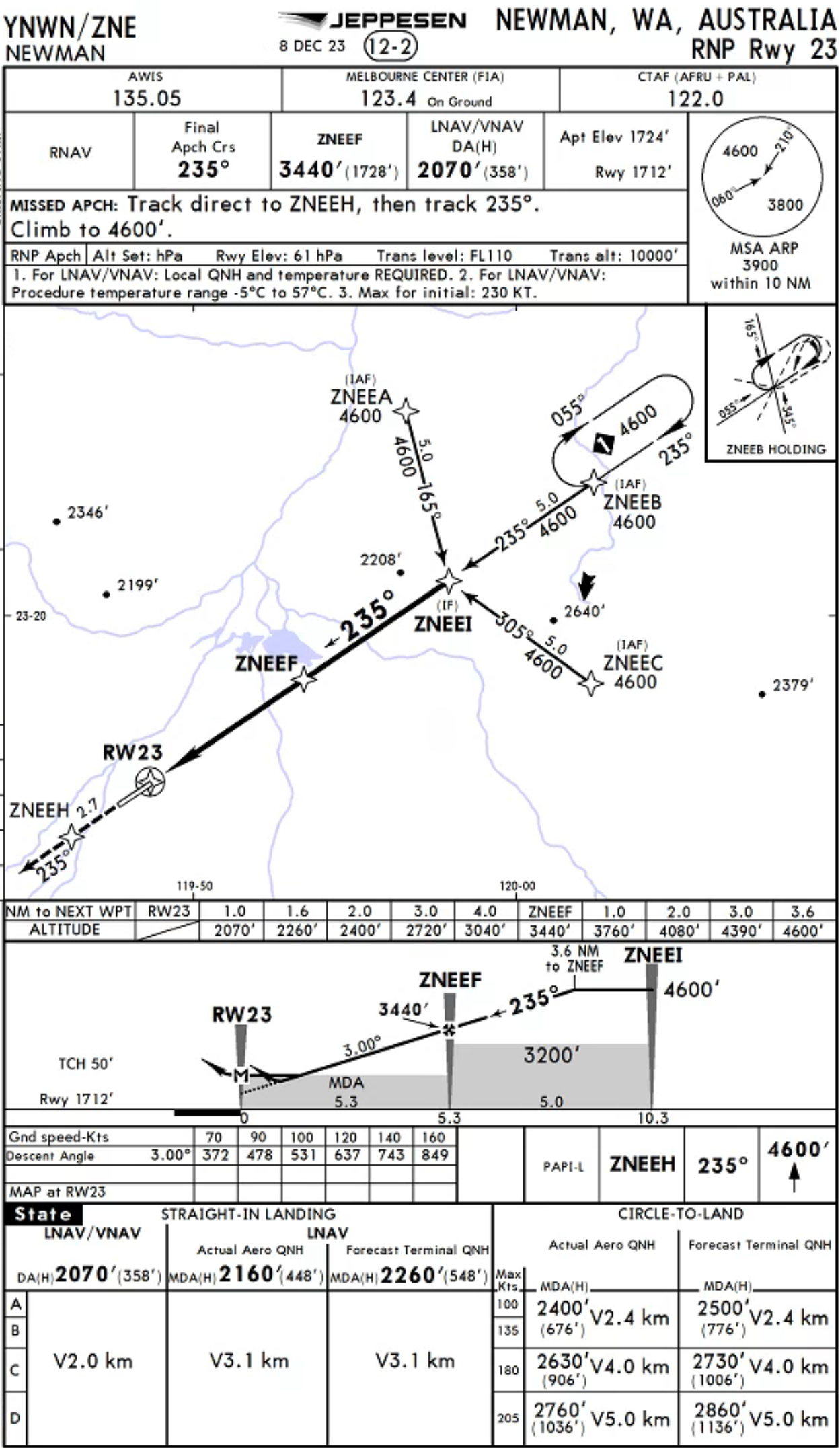

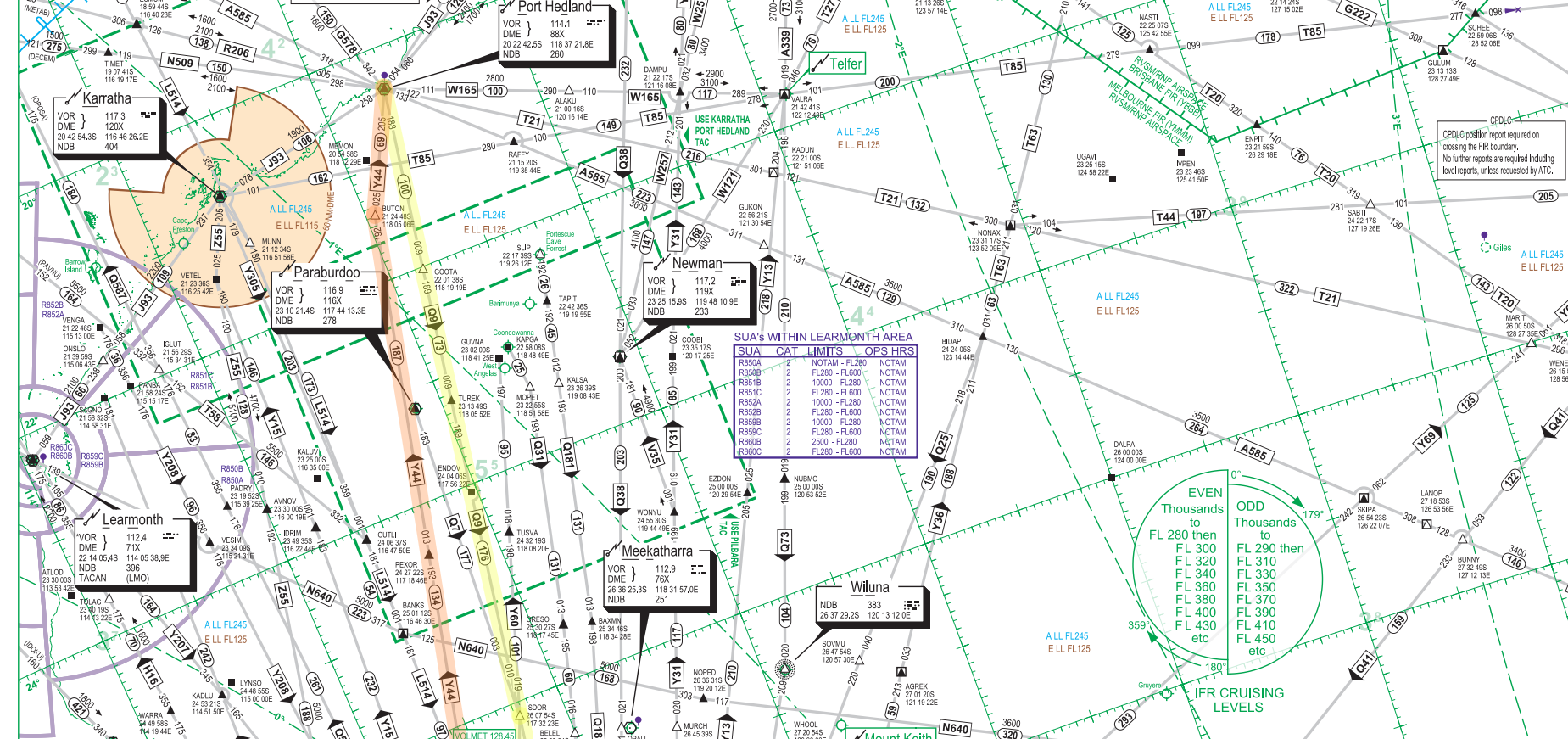

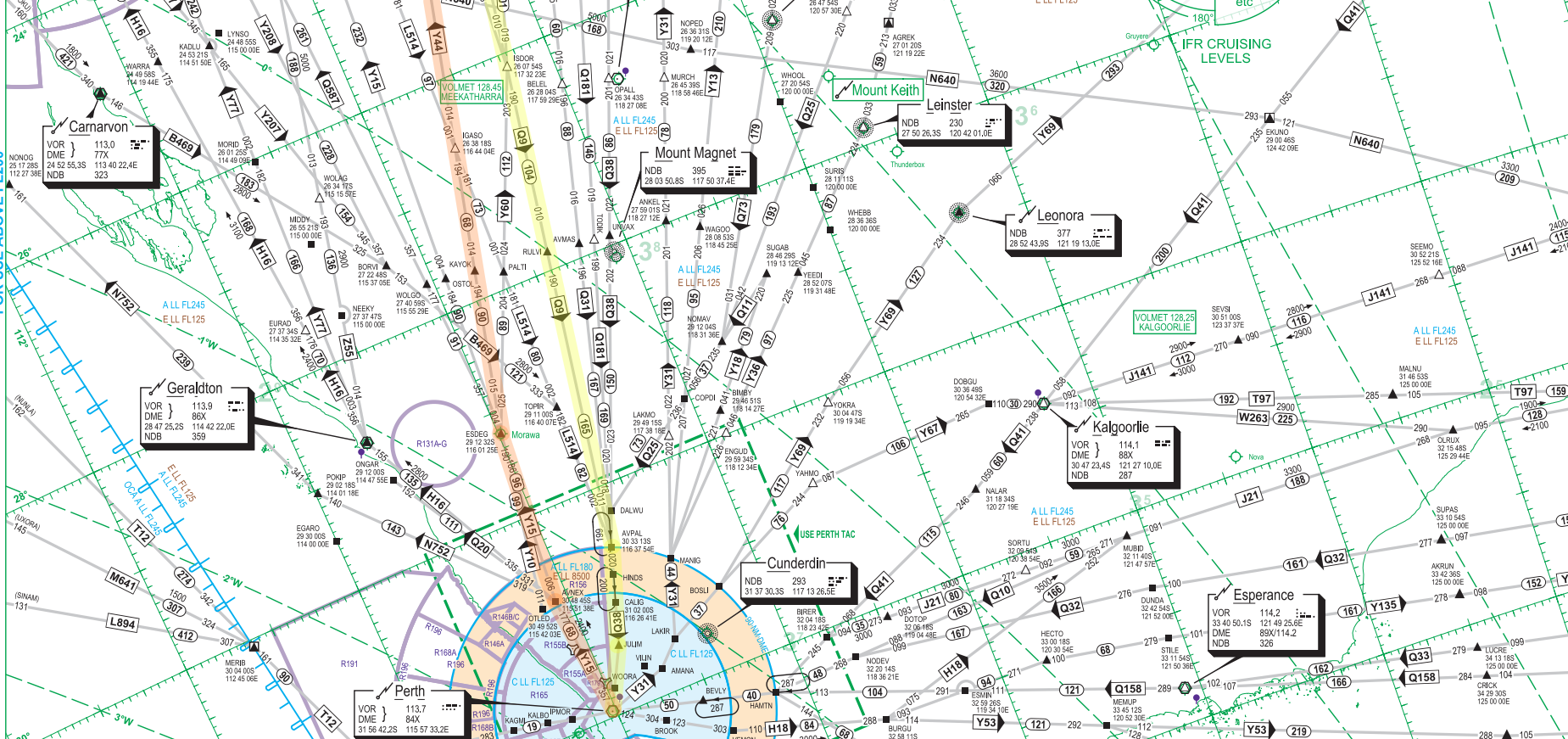

I’ll be covering 4 of these airports in detail below, including their approach and departure procedures, things to take note of when operating into these “hot and high” airports, with temperatures reaching up to 40 degrees Celsius and airfield elevations of up to 2000 feet. This, together with the short runways of only about 2000 metres makes operating into these airports exciting, with tight aircraft performance margins that required good planning to ensure we stay within limits. We’ll discuss fuel tankering, air traffic services, as many of these FIFO airports are in uncontrolled airspace – in the Pilbara, the airspace is largely uncontrolled below FL125.

The following list contains airports in WA that have addons for them in MSFS 2020, but are serviced by Fokker 70/100s in real life, instead of 737s and A320s. When JustFlight releases their Fokker 70/100, likely sometime in 2024, we’ll have a go at operating into these airports!

1 . Telfer Airport Airport (YTEF/TEF)

2. Paraburdoo Airport (YPBO/PBO) (MSFS 2020 World Update 7)

3. Barrow Island Airport (YBWX/BWB)

4. Mount Keith Airport (YMNE/WME)

5. Laverton Airport (YLTN/LVO)

Additionally, many of these FIFO flights stop in certain towns and cities before continuing onto their destinations, in order to pick up or drop off workers who live there. Currently, there are 3 of such aerodromes. I’ve also included Perth itself in the list.

1 . Perth International Airport (YPPH/PER)

2. Albany Airport (YABA/ALH) (Fokker 100 service only)

3. Geraldton Airport (YGEL/GET)

4. Busselton Airport (YBLN/BQB)

Note: A few of these airports have multiple versions available from different developers, notably Perth and Kalgoorlie-Boulder. I’ve included the link for what I think is the best version, out of all the ones available. I must however note that while the Axonos rendition of Perth is the best among all the versions available, there is a free version you might wish to check out. Axonos’ Perth is also available from a few web stores which can be found by searching up ‘Axonos YPPH MSFS’ and ‘YPPH MSFS’ on your preferred search engine. Each of these stores may charge different prices and sales taxes, so do pick the option which is the cheapest for you, if you wish to purchase the scenery.

No One’s Home? No Problem!

A large proportion of these FIFO airports are uncontrolled aerodromes, which means there is no active Tower, and we are in Class G airspace, where no air traffic control (ATC) clearances are required to operate in such airspace. Nevertheless, the Australia Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP) has a fairly detailed set of procedures for pilots to follow when operating in Class G airspace, which we shall examine below.

If there are no towered aerodromes in the area, Class G airspace usually exists below Flight Level (FL) 125 in Australia. Above Class G we usually have Class E airspace, which requires ATC clearance to enter.

All uncontrolled aerodromes will have what is known as a Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF). This frequency should be monitored by pilots and intentions should be broadcast on it, so all aircraft operating in the airspace around the aerodrome will have good awareness of the traffic and situation at hand.

Those of us used to your standard IFR flights in controlled airspace may not be quite used or aware of the procedures when operating in controlled airspace, so let’s walk through what we can expect when departing an uncontrolled aerodrome.

Your first call to ATC should be made when taxiing out to the runway for departure. This will include our aircraft type (e.g. Boeing 737), an explicit notice that we are operating under instrument flight rules (IFR), our location (e.g. taxiway A), our destination, and runway we intend to use.

After takeoff, we should establish ourselves on the outbound departure track from our airport to our first waypoint as soon as practicable by extending one of the legs of the circuit to intercept the outbound track. We should aim to do so within 5 nautical miles of the aerodrome, unless there are standard instrument departure procedures, in which case we will follow them. The initial turn after takeoff can be made once past 400 feet above ground level (AGL) if we are visual with the terrain, but is most often done approximately between 1,500 feet and 2,500 feet AGL. This is because all aerodromes in Australia use left-hand circuits unless otherwise specified, and one should not make any turns that are against the flow of circuit traffic, which is 1,500 feet AGL for jet aircraft.

If we are not visual with the terrain we will typically track the extended centreline till reaching the Minimum Safe Altitude, at which point we initiate any turns. It is our responsibility to ensure adequate terrain clearance until we are positively identified by air traffic control and given instructions. During the departure, we should act in a neighbourly manner and avoid overflying noise-sensitive areas, whenever possible. These images illustrate the flight paths taken by different aircraft once airborne, courtesy of Flightradar24.

You can see how after takeoff the aircraft turn to intercept the outbound track from the airport. For reference, the airport elevations of Newman and Port Hedland are 1724 feet and 33 feet above mean sea level respectively.

Out of airports that do not have standard instrument departures, it does require a bit of trickery to automate the process of establishing ourselves precisely on the outbound track as much as possible, and have correct flight guidance through the flight directors. As we are flying in a single-pilot environment in the simulator, we will use custom waypoints to aid us in our flying, which I will cover below.

Once we are safely airborne, we will then call ATC, letting them know the time we departed the aerodrome, our current track, the outbound track from our departure aerodrome we intend to intercept, our intended cruising level, and our estimated arrival time at the first waypoint on our flight plan. ATC will then provide us with our airways clearance and any time restrictions that we need to meet en route.

Once we pass a certain flight level, we will normally be identified on the scopes of the controllers through radar surveillance, and then the flight proceeds as normal with the controller letting us know that we are “identified”.

When arriving into an uncontrolled aerodrome, ATC will clear us to leave the controlled airspace on descent, and this will be done above FL125. Once we are cleared to leave controlled airspace, we then switch over to broadcast and monitor the CTAF frequency, while still monitoring the previous ATC frequency. We make our calls on the CTAF as we approach the aerodrome. In Australia, flight plans are filed to the destination VOR or waypoint, which do not connect to standard instrument approaches into our airport of choice. Thus, we will need to vector ourselves onto the approach or to enter a visual circuit for landing. This is normally done after leaving controlled airspace, though it is common that ATC will clear us to fly direct to the initial approach fix, the first waypoint on out instrument approach.

It is worth noting that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia (CASA) does not recommend straight-in approaches into uncontrolled aerodromes, but in the context of large air transport operations where an extra few minutes of flying a circuit burns a few hundred kilograms of fuel, we will abide by the clause that while straight-in approaches are not recommended standard procedure, we may still conduct them, provided that we do not disturb the flow of circuit traffic. In the FIFO context, most of these aerodromes that we are operating into will likely have us as the sole aircraft operating in the area, so it’ll be up to our discretion to do as we please.

After landing, we will then make a call on the ATC frequency to “cancel SARWATCH” at our arrival aerodrome, a unique practice in Australia where Search and Rescue services will be activated if our aircraft is uncontactable after a certain time has elapsed. SARWATCH is in fact active for all IFR aircraft operating in Australia, but is automatically cancelled when arriving at controlled aerodromes.

Much of the flying, especially the departure, requires a good briefing while stationary on stand, as things happen really quickly and you can’t simply arm LNAV and hit the autopilot at 400 feet AGL – it’s more involved than that! But it does allow you to use features and capabilities you don’t normally use in the FMC to aid you, and when you fly it just right and it all goes well – the sense of satisfaction is pretty unmatched!

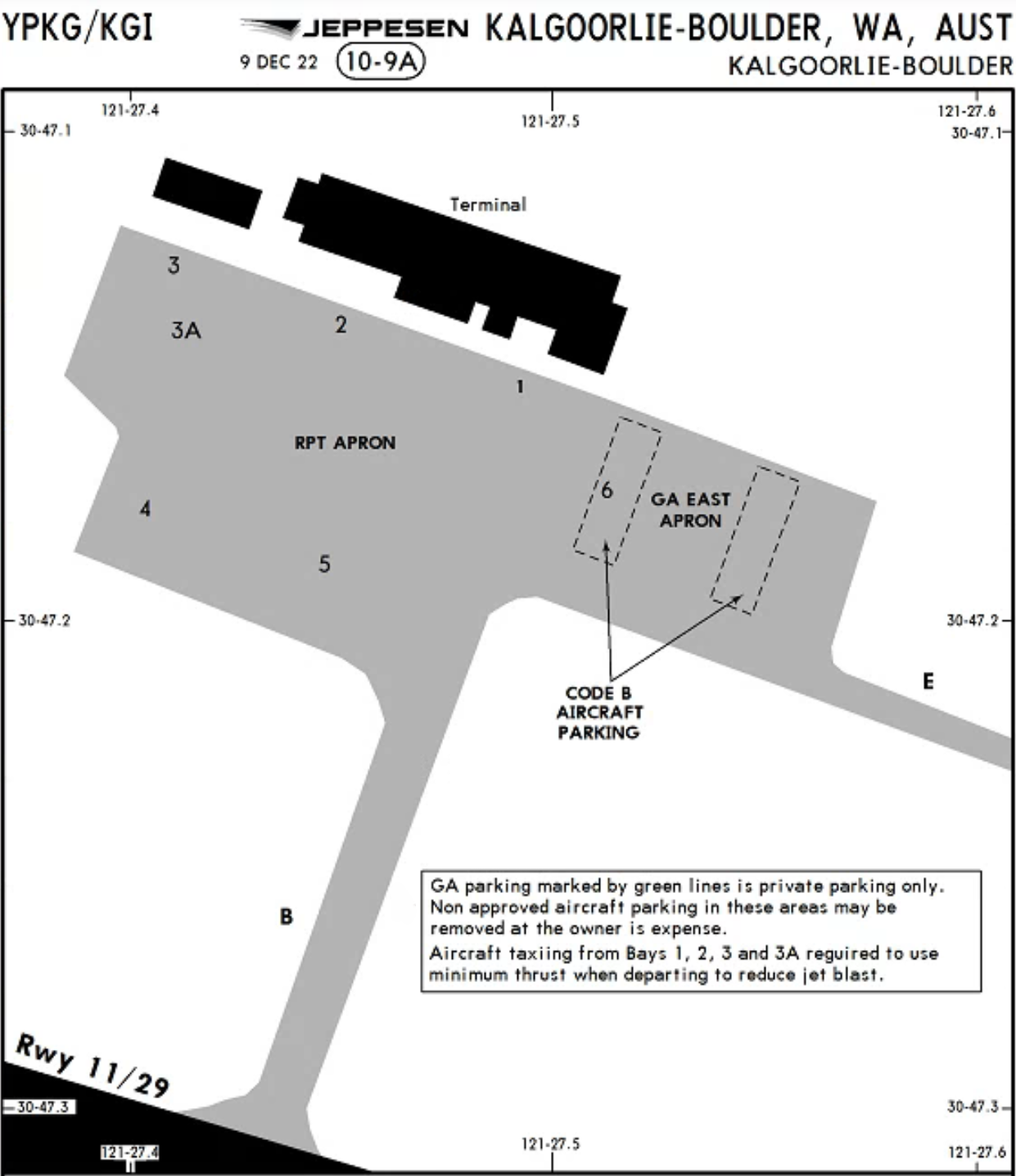

Note: Both charter FIFO flights and regularly public-bookable flights fall under the umbrella category of ‘air transport operations’. There used to be the term ‘regular public transport (RPT)’ to describe the public passenger services but this term is no longer officially in use by CASA as of 2 December 2021. Because RPT was such a widespread term you might still see certain airport charts, diagrams and documents with terms like ‘RPT flights’ and ‘RPT apron’. This will be gradually changed to (check your charts to see what they r called, YBRK, etc.) and was done to streamline the different categories of charter, RPT and air ambulance operations.

Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport (YPKG/KGI)

Let’s start with what is, in my opinion, the best scenery package in MSFS 2020 out of all the FIFO airports in Western Australia.

The airport is located just about 537 kilometres on a bearing of 76 degrees from Perth airport. It receives about 44 flights per week from Perth, which is more than 6 flights a day on average. Both Qantas and Virgin Australia service the route with a wide variety of aircraft, with the A319, A320, 737-700 and 737-800 taking turns to make the relatively short 55-minute hop across the Wheatbelt and into the Goldfields-Esperance region, where Kalgoorlie is located.

https://www.ga.gov.au/education/minerals-energy/australian-mineral-facts/gold

Kalgoorlie is one of the larger and more famous mining towns in Western Australia, with a population of approximately 30,000. Apart from Darwin, there is no city in Australia east of Kalgoorlie with a population larger than itself, until one reaches Adelaide in South Australia. It’s the last stop along the route of the Indian Pacific before arriving at Perth, one of the most famous transcontinental train services in the world, with the journey originating in Sydney.

The history of gold mining in Australia can be traced all the way back to 1823, when the first officially recognised discovery of gold was made in the Bathurst region of New South Wales. While several other discoveries were made in the following years to come, the colonial government in Australia sought to suppress the spread of such news, due to fear that it would cause the then convict-majority population in Australia to abandon their day jobs and move instead to search for gold. This policy was however relaxed after the news of the California gold rush in 1848 spread globally, which enticed officials to instead financially reward those who struck gold.

The gold rush in Australia then officially began in February 1851, when prospectors found gold in Orange, New South Wales. The news soon spread across the nation, and soon more gold was found in the neighbouring state of Victoria in July of the same year. In just a few short months to follow, various other discoveries and mines would spring up across Victoria and New South Wales. These gold rushes sparked immense interest from prospectors all over the world, and caused the population of Australia to quadruple over just 20 short years, rising from 430,000 to 1.7 million from 1851 to 1871. This also transformed the country from what was a group of convict colonies into progressive cities, with many of those who immigrated but were unsuccessful in their search for gold deciding to stay and contribute to the economy with the skills and trades they brought from abroad. This changed the course of Australian history, setting it on track to become what we see today.

Kalgoorlie likewise sprung up as a direct result of the gold rush, but not until a few decades later. In June 1893, a group of 3 Irish prospectors – Paddy Hannan, Thomas Flanagan and Daniel Shea were headed for Mount Yuille, known presently as Mount Youle, due to rumours of gold deposits in the area. They were part of a group of prospectors who had set up camp for the night about 25 kilometres away from their intended destination. To date, there are multiple versions of the story, but it is agreed upon that the 3 men first found gold nuggets in the area, but hid their find till Hannan had a chance to head to Coolgardie, a town located about 40 kilometres southeast of today’s Kalgoorlie, to register their claim. This caused great excitement almost immediately, with prospectors heading out to the area of the find over the next few days. The area saw a huge influx of miners, with 1,400 of them working in the gold fields just a week after the discovery was announced.

What is less commonly known, but perhaps of even greater significance, is that just a few short weeks later, Will Brookman and Sam Pearce arrived from Adelaide, similarly in search of gold deposits. They only received news of the 3 Irishmen’s discovery after arrival in Coolgardie, and hence decided instead to prospect at a few low hills, just a few kilometres south of the original find. They soon discovered even larger deposits, and like before, prospectors rushed to the area, setting up mining camps next to the findings. This mining camp soon grew into what was to become the town of Boulder, and the hundreds of underground mines that eventually opened next door came to be known as the “Golden Mile”.

Kalgoorlie was officially gazetted in September 1894, with Boulder to follow in December 1896. Since then, with the influx of workers and the promise of riches from gold mining, the two towns continued to steadily expand over the next century. Kalgoorlie and Boulder were officially merged to form the city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder in January 1989, though the area is often still referred to as simply Kalgoorlie.

In March 1989, the Fimiston Open Pit, known commonly as the Super Pit gold mine, was born after attempts were made in the 1980s to consolidate the underground mines in the Golden Mile. Today, Kalgoorlie Consolidated Gold Mines Pty Ltd, which operates the Super Pit, employs approximately 1,200 workers, and is Kalgoorlie’s largest employer. Regular blastings still take place at the Super Pit, viewable to the public through a lookout at the mine site. The Super Pit has produced more than 1.4 million kilograms of gold since its opening in 1989, and is responsible for about 8% of Australia’s gold production. Prior to the consolidation of the mines, the Golden Mile produced in total more than 1.1 million kilograms of gold, having been one of Australia’s largest producers of the commodity during its tenure.

The city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, the airport, and the open-cut Super Pit gold mine all in one shot. At 3.5 kilometres long, 1.5 kilometres wide and 0.6 kilometres deep, it really gives you a sense of scale for just how large the Super Pit is.

The airport itself is located right next to the city, with 2 runways, 11-29 and 18-36. Runway 18-36 is only used by smaller propeller-driven aircraft, with runway 11-29 being the one used by jet aircraft. Like many of these FIFO airports, there is no taxiway running parallel to the main runway, so arriving jet aircraft will have to backtrack the runway after landing to arrive at the apron. There are 5 bays available for jet aircraft, all of which are self-manoeuvring stands with no pushback available.

The city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, the airport, and the open-cut Super Pit gold mine all in one shot. At 3.5 kilometres long, 1.5 kilometres wide and 0.6 kilometres deep, it really gives you a sense of scale for just how large the Super Pit is.

The city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, the airport, and the open-cut Super Pit gold mine all in one shot. At 3.5 kilometres long, 1.5 kilometres wide and 0.6 kilometres deep, it really gives you a sense of scale for just how large the Super Pit is.

A showcase of the active mines and resource processing plants in the Kalgoorlie area.

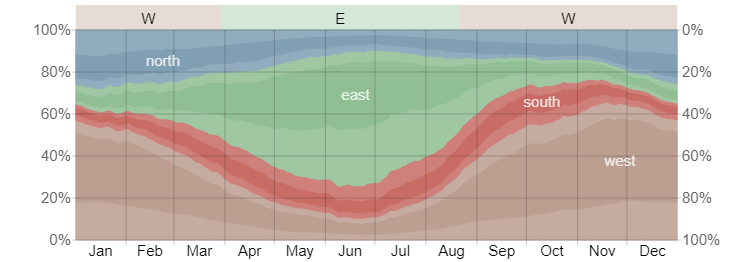

The instrument approaches available into the airport are the RNP 11 and RNP 29 approaches, which are both RNAV approaches with RNP 5 required. The diagram below, courtesy of Weatherspark, shows how during summer months, runway 11 is the most common active runway, with runway 29 taking its place in winter.

The same page shows that the weather is often dry, with infrequent rain. The skies are also often clear, with overcast conditions more likely during summer and autumn. The average daily wind speed is in region of 10 knots, which is relatively mild. Temperatures range between 33 and 19 degrees Celsius during summer, and 16 and 6 degrees during the winter months.

The airport in also home to the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS), a non-profit organisation which flies doctors and patients in and out of remote areas where advanced medical facilities are unavailable. Kalgoorlie is used as a base, where aircraft depart to pick up patients with a doctor on board, and then head to Perth if necessary for medical treatment. The RFDS operates a fleet of propeller-driven aircraft including the PC-12, and has bases all over Australia, allowing them access into even the most remote of regions.

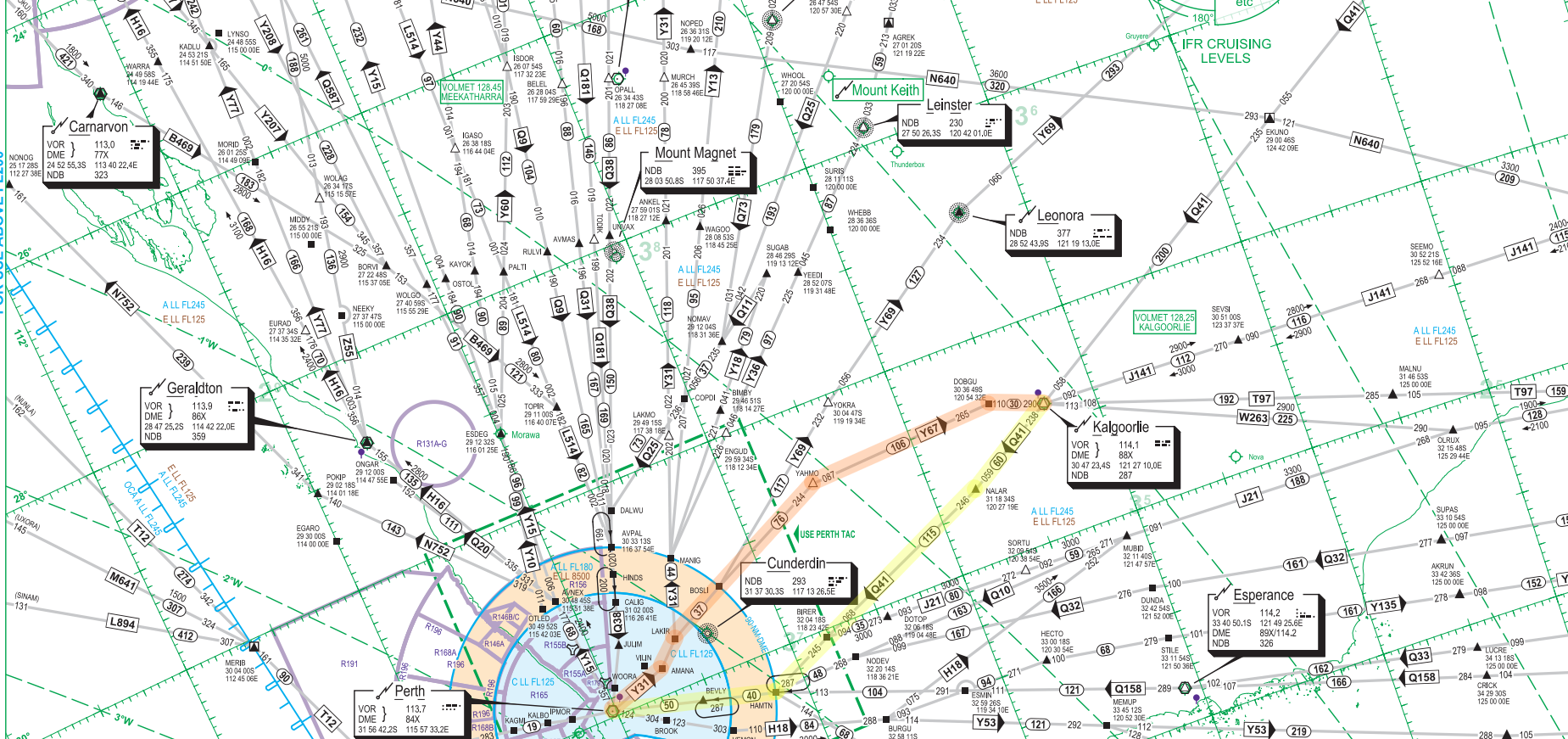

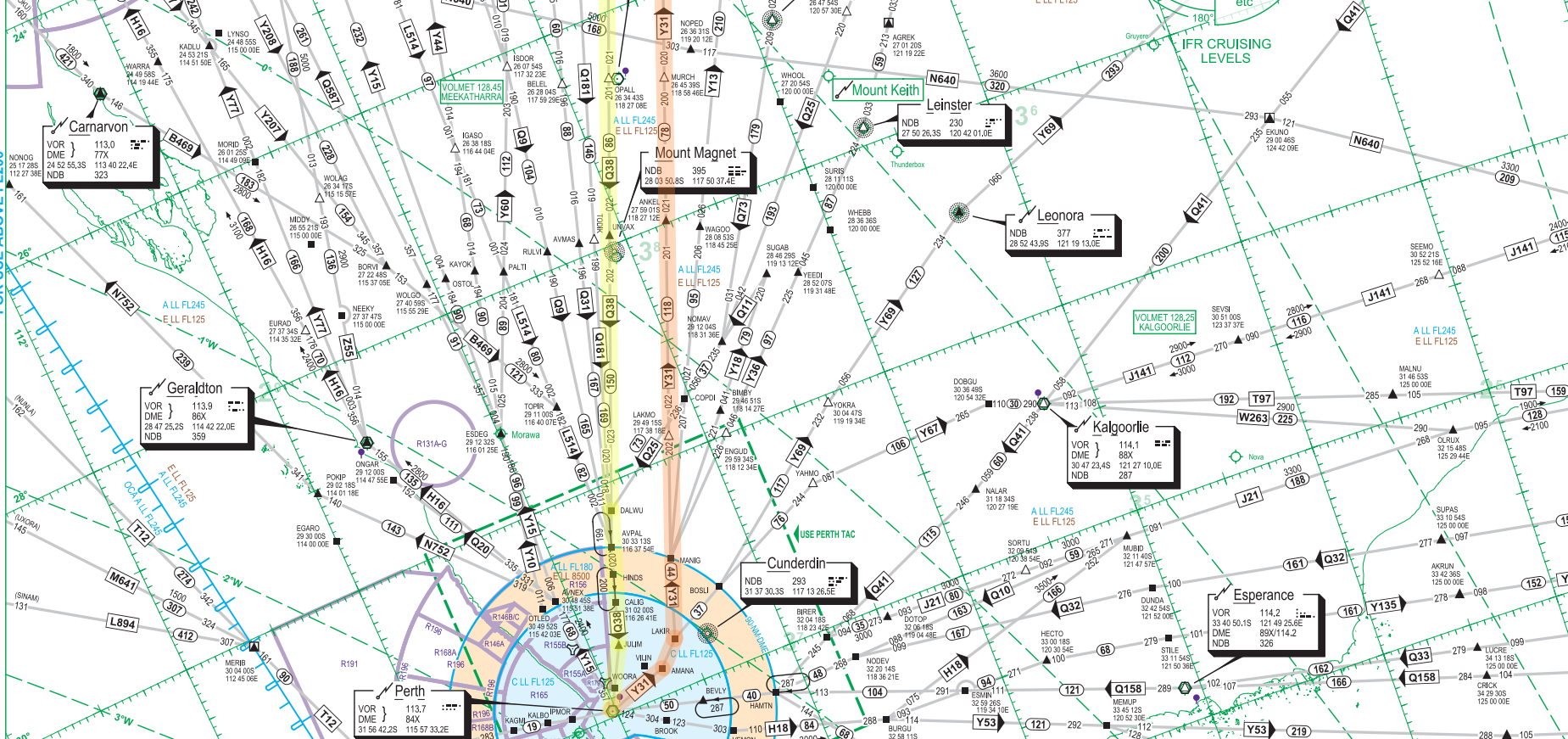

Like many of these FIFO airports, there are no standard instrument departures out of Kalgoorlie. Pilots will depart in accordance to IFR procedures and establish themselves on the departure track outbound from the Kalgoorlie VOR. Once safely airborne and established on the filed routing, they will then contact Melbourne Centre for their airways clearance to their destination, most likely Perth. The standard airways routing would be KG Q41 HAMTN Q158 PH, linking the Kalgoorlie VOR to the Perth VOR through the Q41 and Q158 airways to join the BEVLY5A/V/X arrival into Perth.

It is then up to the aircrew on whether a left or right turn will be executed after departure from runway 11, although a left turn would put the aircraft on a climb right over the city of Kalgoorlie, which would be fairly noisy for the residents. The pilots broadcast their intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and maintain separation from other traffic in the area and terrain, as they climb through the uncontrolled Class G airspace up to Flight Level (FL) 125.

NZA Simulations’ rendition of Kalgoorlie Airport does indeed do the airport justice, with the Super Pit gold mine modelled, along with a decent level of texturing and modelling of the terminal building. While there is no interior, and the airfield floodlighting could see some improvement, it is overall a very faithful recreation of Kalgoorlie.

At 600 metres deep, the Super Pit is more than 70% the height, or rather depth, of the Burj Khalifa. Think of just how crazy the scales are, with the city of Kalgoorlie right next door! Even the airport with a 2,000-metre runway looks tiny in comparison to the mine.

Leonora Airport (YLEO/LNO)

Let’s start with what is, in my opinion, the best scenery out of all the FIFO airports in Western Australia.

The airport is located just about 615 kilometres on a bearing of 57 degrees from Perth airport. It receives about 9 flights per week from Perth, which is just over 1 flight a day on average. Virgin Australia services the route with 737-700s, while Alliance Airlines does so with Fokker 70/100s. The flight time from Perth is just about 1 hour tracking northeast over the Wheatbelt into the Goldfields-Esperance region. The standard airways routing from Perth to Leonora is PH Y31 KARAB Y69 LEO, with the aircraft leaving controlled airspace on descent tracking towards the Leonora VOR, before establishing itself on an instrument approach or visual circuit.

Much like Kalgoorlie, Leonora is a mining town, with prospectors discovering gold deposits in the 1890s, and hence establishing the town to begin their mining operations. It is however a much smaller settlement, with a population of approximately 1,600. Various mines in the are include

The town of Leonora, the airport, with two historic mine sites, Harbour Lights Mine and Tower Hill Mine visible. The continuous road you see running across the image from the left side to the top right side is the Goldfields Highway, which spans 797 kilometres, starting in Meekatharra in the Mid West region of Western Australia and ending in Kalgoorlie.

A showcase of the active mine sites around Leonora.

Let’s have a look at what the weather is like at Leonora Airport. Unfortunately, there is no publicly-reported METAR from an official source, hence, Weatherspark does not have a page on the airport. Nevertheless, we can use this data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology to make our observations. The temperature range during peak summer is between 37 and 22 degrees Celsius, while that during winter is 18 to 6 degrees Celsius. Rainfall is limited, with less than 30 days of rain a year. Winds are around 6 knots on average, with winds generally blowing from the east in the summer, and variable in the winter, with a slight preference for east-west winds.

Similarly, there are no standard instrument departures out of Leonora. Pilots will depart in accordance to IFR procedures and establish themselves on the departure track outbound from the Leonora VOR. Once safely airborne and established on the filed routing, they will then contact Melbourne Centre for their airways clearance. The standard routing to Perth would be LEO Z22 MULDM Z38 KELLA DCT BEVLY Q158 PH, linking the Leonora VOR to the waypoint KELLA through the Z22 and Z38 airways, and then a direct segment to BEVLY, where the aircraft will join the BEVLY5A/V/X arrival into Perth, though the flight plan filed will still include the segment to the Perth VOR via the Q158 airway.

A left turn after departure from runway 04 is preferred, in order to avoid overflying the town. The pilots broadcast their intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and maintain separation from other traffic in the area and terrain, as they climb through the uncontrolled Class G airspace up to Flight Level (FL) 125.

The current version of Leonora is done by CoolGunS, and represents the real-life airport fairly accurately, with the main asphalt runway and the dirt runway, the small parking lot and various small buildings that make up the airport, as well as Rajah Street that leads up to the town of Leonora.

Argyle Airport (YARG/GYL)

If you’ve ever owned a very rare and highly-prized pink diamond (congratulations), chances are that it passed through the very mine responsible for the existence of this airport.

Sitting at 2,116 kilometres away on a bearing of 37 degrees from Perth airport, Argyle Airport is the furthest of all the FIFO airports we will be exploring, with a flight time from Perth in the region of 2 hours and 40 minutes. It receives just about 1 flight per week from Perth, making it the most infrequently serviced airport out of all the FIFO airports we will be exploring. There’s a good reason for this, which we will be going into below. Virgin Australia services the route with 737-700s instead of Fokker 100s due to the great distance Argyle is away from Perth, which would either exceed the Fokker 100’s range carrying a full load of passengers and cargo, or simply be less economical to operate than the 737-700, because the Fokker 100 would not have much extra capacity to tanker fuel for the return sector back to Perth, as we discussed above in an earlier section.

Argyle sits just south of Lake Argyle, which is the biggest man-made lake in the southern hemisphere. On departure out of runway 01 from Argyle Airport you will be treated to a fantastic view of the lake out of the left side of the aircraft, as you can see in a video below.

Just about 200 people reside in the Lake Argyle locality, approximately half of which have Australian Aboriginal ancestry. Why then does an airport exist? You see, Argyle is unique in our list in that it serves, or rather served, a mine that is no longer active. Mining operations at the Argyle Diamond Mine halted in November 2020, marking the closure of the last operating diamond mine in Australia. Argyle wasn’t just any diamond mine though – throughout its 37-year span of continuous operations, the mine produced 865 million tonnes of rough diamonds, supplying over one-third of the world’s diamonds every year. It was once the world’s largest producer of diamonds, with up to 42.8 million carats at its peak in 1994. The Argyle Diamond Mine is also famous for the exceedingly rare and highly sought-after pink diamond, producing up to 95% of the world’s supply.

To appreciate the history of the mine, we must first understand how diamonds are discovered and mined. You may have heard the motivational phrase “diamonds are made under pressure”, and that is indeed the case, specifically, at around 50,000 times the pressure at sea level and a temperature of approximately 1,200 degrees Celsius. Why do we need such extreme conditions?

If you’ve studied a bit of chemistry, you might know that diamond is made up of the simple carbon atom, much like its more common (and much cheaper) sibling, graphite. In graphite, we see layers of carbon atoms, and in each later, each carbon atom is bonded to three other atoms, with one valence electron free and not involved in the bonding. These free valence electrons form energy bands that are close in energy to each other, and are hence able to absorb small amounts of energy in the form of visible light to make the jump from one band to the other, causing graphite to appear opaque and black as it absorbs almost all visible light.

Unlike graphite, diamond has the property of each carbon atom forming only single bonds with 4 other carbon bonds. As the valence electrons in diamond are all involved in bonding, the next available energy band for them to jump into is much higher, requiring energy outside the visible spectrum of light to excite them, and thus, no visible light is absorbed by diamond, giving them their transparent appearance.

A showcase of the active mine sites around Leonora.

In order for carbon to form the coveted extra bond with a fellow carbon atom, high temperatures and pressures need to be present in order for the formation of diamond from carbon deposits to be energetically favourable over graphite. The exact explanation for this process is complex, but can be simplified to the fact that diamond has a more compact structure due to the extra bond per carbon atom compared to graphite. High pressures thus make diamond the more energetically favourable allotrope of carbon, and the temperatures are high enough to overcome the large activation energies for the formation of diamond to take place. The extreme conditions required for this to happen exist in the earth’s mantle, around 200 kilometres below the surface of the earth.

The diamonds then need to be transported to the earth’s surface rapidly, before they eventually transform into the most stable form of carbon at normal temperatures and pressures – graphite, if they were to slowly make their way up. We don’t have any drills that can reach 200 kilometres deep, let alone economically mine for diamonds at such depths. Hence, we rely on volcanic rocks known as kimberlites and lamproites to transport these diamonds, which are embedded within them, up to the surface of the earth through volcanic pipes formed by the eruption of volcanoes deep underneath the surface of the earth. This is what is eventually mined at the surface of the earth, as the magma solidifies and diamonds can be extracted from the rocks in large amounts.

Typically, diamonds are first discovered along streams and bodies of water, as what are known as alluvial diamonds. These diamonds would have been deposited in the headwaters of a river and eventually make their way downstream from the volcanic pipes through erosive transport, where they would then be uncovered by prospectors. Since the 1890s small amounts of alluvial diamonds have turned up across Australia by those searching for gold, and in the 1970s, systematic searches began in the Kimberley region of Western Australia for the volcanic pipes that were the primary source of the diamonds.

In July 1979, now famous English geologist Maureen Muggeridge discovered diamonds in the floodplains of Smoke Creek, a narrow stream of water that led to Lake Argyle. She then, in secret with her team, worked to trace the origin of the diamonds, and in October 1979, discovered what is presently known as the Argyle pipe. The site was inspected over the next few years, and eventually became the world’s largest known diamond deposit, then containing more diamonds than the rest of the world combined. In 1983, alluvial mining operations began and the open-cut Argyle Diamond Mine was constructed over 18 months, costing 450 million AUD.

A showcase of the active mine sites around Leonora.

The mine opened in 1985 and operations began thereafter, eventually moving from open cut to fully underground operations by 2013. The Argyle Diamond Mine Village was constructed about 3 kilometres northeast of the mine, serving as temporary accommodation for the, at its peak, 750-strong workforce employed to work on the mine. As most of these workers were skilled labourers with roles such as engineers and geologists, the Argyle Airport was constructed to bring them in from Perth through FIFO flights, due to the nearest airport capable of handling jet aircraft being the East Kimberley Regional Airport at 188 kilometres away by road. The East Kimberley Regional Airport serves what happens to be the closest permanent settlement to the Argyle Diamond Mine – Kununurra, with a resident population of 4,515.

Mining however eventually became economically unfeasible, due the the exhaustion of all economically viable reserves. After 37 years of operations, the Argyle Diamond Mine ceased operations in November 2020 for good. Rio Tinto, the company that owns and manages the mine, will decommission the site and work together with the Traditional Owners of the land to rehabilitate the surrounding areas over the following 5 years. The now once-weekly flights by Virgin Australia are likely charters for dismantling and restoration crew, which will make up a small part of the 850 million AUD in costs required for the cleanup of the site, which will be footed by Rio Tinto. This figure, as large as it sounds, is but a small fraction of the total revenue generated by the mine, with over 370 million AUD in 2018 alone.

The Argyle Diamond Mine (ADM) on the left, the ADM Village in the centre, and Argyle Airport in the top right corner of the image. The body of water you see to the top left of the image is where Smoke Creek originates, and it’s no coincidence that it’s right next to the mine site!

The instrument approaches available into the airport are the RNP 01 and RNP 19 approaches, which are both RNAV approaches with RNP 5 required. Data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology shows that there is a preference for northeasternly winds during the summer months, with mornings seeing an equal chance of southernly winds too. During winter, the winds shift to blow almost exclusively from the southeast. ter. The skies are mostly clear during winter, whereas an even split between cloudy and clear is seen during the summer months. The average daily wind speed is in region of 7 knots. Notably, winter months tend to have the strongest morning winds but weakest afternoon winds, while summer months see the opposite – the weakest winds in the morning and strongest in the afternoon.

The Argyle Diamond Mine (ADM) on the left, the ADM Village in the centre, and Argyle Airport in the top right corner of the image. The body of water you see to the top left of the image is where Smoke Creek originates, and it’s no coincidence that it’s right next to the mine site!

Due to the more coastal location of Argyle, it experiences more rainfall than its inland counterparts, with an average of 53 days of rain a year, with about 10 days a month during the summer months. This does however fall to almost 0 in winter. The maximum and minimum mean temperature ranges are between 39 and 26 degrees Celsius, interestingly, during spring, and 30 and 16 degrees during the winter months. The likely explanation for the maximum mean temperature being in spring instead of summer is likely due to sharp increase in rainfall in the summer months – almost thrice as much, hence lowering the average temperatures.

There are no standard instrument departures out of Argyle. Pilots will depart in accordance to IFR procedures and establish themselves on the departure track outbound from the Argyle VOR. Once safely airborne and established on the filed routing, they will then contact Melbourne Centre for their airways clearance to their destination. For aircraft bound for Perth, the standard airways routing would be ARG T63 BIDAP Q25 DALWU Q38 PH, linking the Argyle VOR and the Perth VOR, where the aircraft will eventually be given STAR clearance for the JULIM5A/V/X arrival into Perth.

It is then up to the aircrew on whether a left or right turn will be executed after departure from runway 11, although a left turn would put the aircraft on a climb right over the city of Kalgoorlie, which would be fairly noisy for the residents. The pilots broadcast their intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and maintain separation from other traffic in the area and terrain, as they climb through the uncontrolled Class G airspace up to Flight Level (FL) 125.

The current version of Argyle Airport is done by CoolGunS. It is a faithful rendition of the fairly small airport, with only a single runway, an apron capable of handling two aircraft and some buildings to its name.

The Argyle Diamond Mine (ADM) on the left, the ADM Village in the centre, and Argyle Airport in the top right corner of the image. The body of water you see to the top left of the image is where Smoke Creek originates, and it’s no coincidence that it’s right next to the mine site!

Argyle Airport in the foreground, with the entirety of Lake Argyle visible in the image. Smoke Creek itself is also visible, which is the thin stream of water, sometimes dry, running to the left of the airport and up north into the lake. It leads down south right to where the Argyle Diamond Mine is.

A shot looking north-northeast, with the Argyle Diamond Mine, Argyle Airport and Lake Argyle visible

Newman Airport (YNWN/ZNE)

The airport with likely the most relevance to what our modern lives – sitting just south of what is regarded to be the birthplace in Australia of the product that makes up 95% steel, a key component to just about every single piece of modern infrastructure around us today.

The airport is located just about 1,020 kilometres away on a bearing of 22 degrees from Perth airport. It receives about 40 flights per week from Perth, which is just under 6 flights a day on average. Both Qantas and Virgin Australia service the route with a wide variety of aircraft, with the A319, A320, 737-700 and 737-800 taking turns to make the 1 hour and 30 minute-hop across the Mid West and into the Pilbara, where Newman is located, together with many of the other FIFO airports we will be exploring.

A shot looking north-northeast, with the Argyle Diamond Mine, Argyle Airport and Lake Argyle visible

https://www.ga.gov.au/education/minerals-energy/australian-mineral-facts/iron

Newman is one of the larger mining towns in the Pilbara. In fact, it is the third largest largest in terms of population, sitting after Karratha and Port Hedland at a resident population of approximately 6,500 residents. A further estimated 4,000 FIFO workers call Newman home when on shift.

Newman, formerly Mount Newman until 1981, can trace its roots back to the discovery of iron ore reserves at the current Mount Whaleback mine. Since the end of World War II, prospectors had been abound in Australia, all in fervent search for extractable materials which would make them their fortunes. Among those was Stan Hilditch, a manganese prospector, who went about searching in Western Australia for the material, backed by entrepreneur Charles Warman. Hilditch focused on hilly sites due to a belief that minerals would more easily precipitate in such terrain due to geological processes. As it turned out to be, he was right – after summitting Mount Whaleback in 1957, he soon realised through analysis of the rocks in the area that he was standing on a huge amount of iron ore reserves. The discovery however, was not of much use to him, as at that point in time, the Australian government had in place an embargo on the export of iron ore, due to the belief (in hindsight, humourous in nature) that Australia might be short on such a resource.

The break came in 1961, when the embargo was lifted. However, things were not particularly smooth-sailing, as no major company was interested in funding the exploration and mining of the area, due to the remote location of the site, which meant a large distance from a shipping port for export and the lack of a large-enough workforce for the mining and processing of the ore. Two years of frustrating and futile negotiations followed, until eventually in 1963 when AMAX, an American metal production company, agreed to explore the site, with Hilditch and Warman selling their 358,000-hectare temporary reserves for 10 million AUD. AMAX eventually collaborated with other mining companies including BHP and CSR to form the Mount Newman Mining Company to explore and develop the mine site.

The mine was eventually opened in 1968, following the construction and establishment of the town of Mount Newman in 1966 to provide residence for employees working on the development of what would become the largest open-pit iron ore mine in the world. Since then, supermarkets, schools, a hospital, entertainment centres and various other amenities have sprung up, turning Newman into a proper mining town, which provides goods and services to other mining settlements and mines in the region such as Roy Hill, Solomon, Paraburdoo and Area C. Mount Whaleback itself is no more, with what once made up the distinctive hump that gave it its name now all over the world, especially in China, Japan and South Korea, in the form of solid steel.

Newman Airport in the foreground, with the town of Newman ahead of it, about two-thirds of the image up. The town is approximately 11 kilometres away from the airport by road, which would take just over 10 minutes to cover. The Mount Whaleback mine, which is majority-owned by BHP, sits just west of Newman and is visible in greater detail below.

Newman Airport in the foreground, with the town of Newman ahead of it, about two-thirds of the image up. The town is approximately 11 kilometres away from the airport by road, which would take just over 10 minutes to cover. The Mount Whaleback mine, which is majority-owned by BHP, sits just west of Newman and is visible in greater detail below.

The instrument approaches available into the airport are the RNP 05 and RNP 23 approaches, which are both RNAV approaches with RNP 5 required. The diagram below, courtesy of Weatherspark, shows that runway 05 is the most common active runway during most of the year, with an even split during the spring months. Data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology also shows that throughout the year, mornings see more frequent winds that favour runway 05.

As expected in the Pilbara, rain is infrequent, especially in winter. The skies are mostly clear during winter, whereas an even split between cloudy and clear is seen during the summer months. The average daily wind speed is in region of 8 knots. Temperatures range between 40 and 25 degrees Celsius during summer, and 23 and 8 degrees during the winter months. Newman offers some of the more extreme temperature variations throughout the day in Australia, as its inland location offers both raid cooling and rapid heating without large bodies of water nearby to regulate the temperatures.

There are no standard instrument departures out of Newman. Pilots will depart in accordance to IFR procedures and establish themselves on the departure track outbound from the Newman VOR. Once safely airborne and established on the filed routing, they will then contact Melbourne Centre for their airways clearance to their destination, most likely Perth. The standard airways routing would be NWN Q38 PH, linking the Newman VOR to the Perth VOR through the Q38 airway, where aircraft will eventually be given clearance to fly the JULIM5A/V/X arrival into Perth.

It is then up to the aircrew on whether a left or right turn will be executed after departure from runway 11, although a left turn would put the aircraft on a climb right over the city of Kalgoorlie, which would be fairly noisy for the residents. The pilots broadcast their intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and maintain separation from other traffic in the area and terrain, as they climb through the uncontrolled Class G airspace up to Flight Level (FL) 125.

The current version of Newman is done by CoolGunS. The main terminal building with the solar panels is modelled, along with the various parking spaces used for the trailers and hordes of rental vehicles.

Newman Airport in the foreground, with the town of Newman ahead of it, about two-thirds of the image up. The town is approximately 11 kilometres away from the airport by road, which would take just over 10 minutes to cover. The Mount Whaleback mine, which is majority-owned by BHP, sits just west of Newman and is visible in greater detail below.

The town of Newman in the foreground, with Newman airport roughly 10 kilometres ahead. You can see the East Pilbara Race Club on the left, complete with its dirt racehorse track, as well as Hillview Speedway Club’s motorsports dirt track to the right of Newman, both of which host regular events throughout the year. There’s also a golf course, various sports fields and parks, which must surely be fairly challenging to maintain in the hot and dry climate. The road you see running up from the bottom of the image and turning right into the distance just before Newman Airport is the Great Northern Highway. Spanning 3,195 kilometres, it is Australia’s longest highway and connects Perth, via Port Hedland and Broome, to Wyndham, the northernmost town in Western Australia.

The Mount Whaleback mine, sitting at 5.5 kilometres log and 1.5 kilometres wide, is capable of producing over 70 million tonnes of iron ore yearly

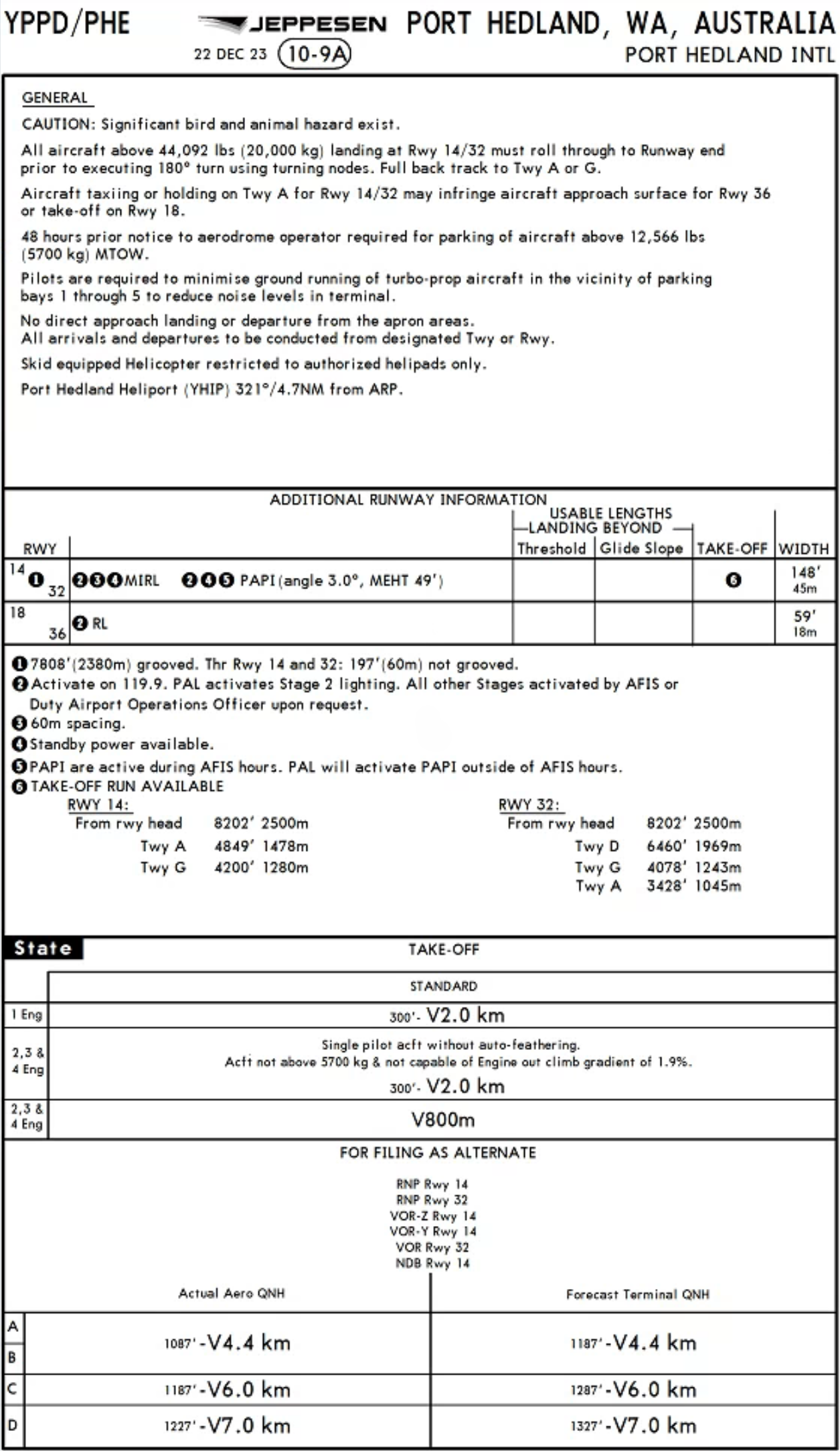

Port Hedland International Airport (YPPD/PHE)

Last but most certainly not least, we have the airport whose name is synonymous with what brings much of Australian iron ore to the world, and has made itself world-famous while setting out on its mission to do so.

The airport is located about 1,313 kilometres away on a bearing of 12 degrees from Perth airport. It receives about 49 flights per week from Perth, which is approximately 7 flights a day on average. Both Qantas and Virgin Australia service the route with a wide variety of aircraft, with the A319, A320, 737-700 and 737-800 taking turns to make the 1 hour and 45 minute-hop across the Mid West, the Pilbara and up to the coast where Western Australia meets the Indian Ocean.

Sitting at a population of approximately 17,000, Port Hedland is the second largest city in the Pilbara, after Karratha, and the 8th largest in Western Australia. Most of the development and existence of the town can be attributed to the, you guessed it – port of Port Hedland, which is the largest bulk cargo port in Australia.

The port can trace its beginnings to the arrival of Swedish explorer Captain Peter Hedland in April 1863, where he discovered and described the natural harbour that came to be named Port Hedland in his honour. The port initially served as a point of entry and exit for the shipment of raised cattle and poultry in the Pilbara. Soon after, pearl harvesting boats, known as pearling luggers, began using Port Hedland as a stopover point in the late 1870s. Their crew began to settle down in the area, with over 150 luggers and their crews calling Port Hedland home.

In the 1880s during the gold rush in Western Australia, the port began to play an important role as a shipment port for the gold that was prospected in the Marble Bar and Nullagine goldfields, located about 200 kilometres southeast of Port Hedland. This development led to an increase in the resident population of the town, and Port Hedland was formally surveyed and gazetted in 1896. Throughout the following few decades, the town gradually grew in size, with more facilities to its name and more connections to the rest of the state, fuelled by the export of gold. Railways, schools, hotels, churches and other such infrastructure was constructed during this time, including the beginnings of what was to become Port Hedland International Airport.

In the 1950s with the exploration and discovery of manganese deposits after World War II in places such as Woodie Woodie, about 300 kilometres southeast of Port Hedland, there was further growth and expansion of both the port and the town itself. Manganese was the first bulk commodity to have been exported from Port Hedland, paving the way for what was to follow.

But the big explosion in the town’s development and population is almost entirely owed to one thing that you might have already guessed – the discovery of rich iron ore deposits in the Pilbara. In 1961 with the lifting on the export embargo on iron ore, Port Hedland’s position as the largest and closest established port to the iron ore mines in the Pilbara invited huge investments from mining corporations such as BHP. The biggest development uptick took place in 1965, when the town of approximately 1,200 people then rapidly expanded in both population and area, with South Hedland springing up, as well as a large expansion in the quality and scale of the infrastructure. Goldsworthy Mining Limited, which would later be absorbed by BHP, dredged an approach channel and turning basin, in order for the port to play host to some of the largest ships in the world, with capacities of up to 60,000 deadweight tonnes (DWT). In March 1969, the first load of iron ore was officially shipped out of Port Hedland on its journey to Japan.

Courtesy of the Pilbara Ports Authority

The rest, as they say, is history with the port of Port Hedland today being the largest bulk export port in the world, with 19 berths capable of handling ships with a capacity up to 320,000 DWT. The port recorded a tonnage of 566.5 million in 2023, generating approximately 64 billion AUD in export value and accounting for about 57% of Australia’s resource exports.

An entire railway network was constructed by the various mining companies to transport the processed resources to Port Hedland for export. BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals Group (FMG), which are the 3 largest mining companies in Australia by market capitalisation, all operate private railways linking their sites to the various ports for export. Port Hedland is used by BHP, FMG and others, whereas Rio Tinto exclusively uses Dampier and Cape Lambert, located about 200 kilometres west of Port Hedland.

Courtesy of Reuters

The trains which run these lines are some of the longest and heaviest in the world, with a freight train operated by BHP in June 2001 holding the world record for the longest train ever recorded, at a staggering 7.353 kilometres long, comprised of 8 locomotives and 682 cars loaded up with iron ore. It weighed an incredible 99,734 tonnes. For reference, the Airbus A380 has a maximum takeoff weight of just 575 tonnes – that’s more than 173 times less than the record-breaking train. Such trains will take a few kilometres to perform a full emergency stop – at nominal speeds of 75 kilometres per hour, the amount of kinetic energy held would be 21.6 gigajoules, which is equivalent to the amount of energy released by 5,173 kilograms of TNT!

This graphic from Peter Christener, hosted at the Wikimedia Commons, very nicely shows the various railway lines and how they link to the ports

The port of Port Hedland when viewed from above. Unfortunately you can’t quite see any ships in this shot, but they usually line the interior of the central body of water in the image. The Port Hedland Turf Club, located on the site of a former airfield, is very much visible – it’s the oval-ish green pitch next to the port in the rightmost quarter of the image.

Port Hedland International Airport has a long history spanning over 100 years, with humble beginnings back in 1921, when an airfield was developed at the site of the current Port Hedland Turf Club. Western Australian Airways operated flights that formed the first air link between the town and Perth, with stops in Geraldton, Carnarvon for the night, then Onslow and Roebourne, before finally arriving in Port Hedland after 2 days of flying.

In 1940, an aerodrome was built on the site of where the airport is today. The terminal was very primitive in terms of construction and design – it had a spinifex roof, which a type of grass, and was cooled with water bags. This turned out to be fortunate, as the 70 bombs dropped on the airport during World War II caused severe damage to the runways and surrounding buildings, and eventually in 1956, the terminal was replaced with a new fibre cement building.

Following the explosion in Port Hedland’s population and the dramatic increase in the number of workers arriving in the 1960s thanks to iron ore exports through its port, a brand-new airport terminal building was constructed in 1971. The airport gained international status in 1982 with flights to Denpasar in Indonesia operated by Garuda Indonesia and Qantas. Throughout the next few decades, regular upgrades to the airport have been undertaken to cater for the increased passenger traffic. Most recently in 2019, an 18 million AUD airside infrastructure upgrade took place that involved the construction of a new taxiway, the resurfacing of the apron and new lighting, among other upgrades. This was followed by a 25 million AUD refurbishment to the passenger terminal in 2021 that was completed in 2023.

The RFDS also operates a base in Port Hedland, having begin operations in October 1935, with gradual expansions in equipment and presence through the coming years. The base serves much of the Pilbara and Gascoyne regions, with the next 2 nearest bases in Meekatharra in the Mid West and Broome in the Kimberley, which are 690 kilometres to the south and 460 kilometres to the northeast from Port Hedland respectively

A shot containing Port Hedland International Airport, South Hedland and Wedgefield, 2 localities which make up the town of Port Hedland, as well as the port of Port Hedland. BHP’s Port Haven village and the Compass Group’s ESS Waypoint Village which provide accommodation for FIFO workers are also visible, located conveniently right next to the airport.

A shot containing Port Hedland International Airport, South Hedland and Wedgefield, 2 localities which make up the town of Port Hedland, as well as the port of Port Hedland. BHP’s Port Haven village and the Compass Group’s ESS Waypoint Village which provide accommodation for FIFO workers are also visible, located conveniently right next to the airport.

A shot containing Port Hedland International Airport, South Hedland and Wedgefield, 2 localities which make up the town of Port Hedland, as well as the port of Port Hedland. BHP’s Port Haven village and the Compass Group’s ESS Waypoint Village which provide accommodation for FIFO workers are also visible, located conveniently right next to the airport.

The instrument approaches available into the airport are the RNP 14 and RNP 32 approaches, which are both RNAV approaches with RNP 5 required. The diagram below, courtesy of Weatherspark, shows a very clear seasonal preference for wind direction, with east and southeasterly winds by the most common in winter, and west and northwesterly winds dominating in summer. It is then no surprise that the runways are oriented in a northwest-southeast direction. Data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology also shows that throughout the year, mornings see more frequent winds that favour runway 05.

With Port Hedland right on the coast of the Indian Ocean, it experiences more mild temperatures and an overall cloudier and wetter climate. Skies are partially cloudy throughout the year with the exception of summer, where it is frequently overcast or mostly cloudy. The average daily wind speed is in region of 9 knots. Temperatures range between 35 and 25 degrees Celsius during summer, and 26 and 14 degrees during the winter months. Port Hedland sees a peak of about 8 days of rain in February, falling to less than 1 day per month during the winter and spring months.

There are no standard instrument departures out of Port Hedland. Pilots will depart in accordance to IFR procedures and establish themselves on the departure track outbound from the Port Hedland VOR. Once safely airborne and established on the filed routing, they will then contact Melbourne Centre for their airways clearance to their destination, most likely Perth. The standard airways routing would be PD Q9 AVPAL Q38 PH, linking the Port Hedland VOR to the Perth VOR through the Q9 and Q38 airways, where aircraft will then transition onto the JULIM5A/V/X arrival into Perth. You’ll notice that apart from Kalgoorlie, almost all aircraft from FIFO airports will fly the JULIM arrival into Perth, and indeed, together with the BEVLY arrivals which carry traffic from the east (Cairns, Brisbane, the Gold Coast, Sydney, Adelaide, Canberra, Melbourne, Hobart), the two feeder fixes JULIM and BEVLY will welcome the bulk majority of traffic into Perth.

After takeoff, the flight crew will begin their turn to the west. This can be done once past 400 feet, but pilots will usually delay the turn, especially when departing from runway 32, where a left turn immediately after departure would put the aircraft low over the residential areas to the west of the airport. The pilots broadcast their intentions on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and maintain separation from other traffic in the area and terrain, as they climb through the uncontrolled Class G airspace up to Flight Level (FL) 125.

The current version of Port Hedland is done by CoolGunS. The main terminal building with the solar panels is modelled, along with the various parking spaces used for the trailers and hordes of rental vehicles.

Shots of the airport – the left one looking north and the right one looking south

The two major FIFO villages in Port Hedland – BHP’s Port Haven Village in the foreground and the Compass Group’-operated ‘s ESS Waypoint Village up ahead. These villages are fully serviced with hundreds of ensuite rooms, dining hubs, in-house chefs, sporting and recreational facilities, full mobile and internet coverage, as well as conference, meeting and function rooms. The best part about staying there as a FIFO worker – it’s all free! Or included in your compensation package if you prefer to see it that way.

The locality of Wedgefield – most of the buildings are industrial in nature, with workshops, logistics units, storage facilities and company offices

The locality of South Hedland – you can see the much more orderly layout of the buildings and roads as compared to Wedgefield. Most of the 17,000 residents of Port Hedland live here, together with a few hundred or so FIFO workers in the ESS Gateway Village on the far edge of the locality.

Leave a comment